by TWY

Serenity and Secrets

I discovered Bette Gordon’s 1983 film Variety purely by chance. I found it just like how I walk, how I see, in a way just like anything else I’ve encountered on the streets of New York, an ongoing list that includes: the red door of 916 Union St., Brooklyn; the unspecified “Anna” graffitis all over Manhattan; the arthouse cinemas; the High Line; the invisible loop in Central Park; the beams of light when the Queens-bound 7 train exits the tunnel, etc. No manuals ever, no guides, only pure discoveries. And Times Square, which I ignore as much as possible, yet remains a temptation. After watching the film, it’s only more logical that Times Square is the world center of our 24/7 bombardment of consumerism. It’s only logical that this used to be the kingdom of “adult entertainment,” which has morphed into the signature scenery of tourism and the mainstream — once established, the “pornography” never left.

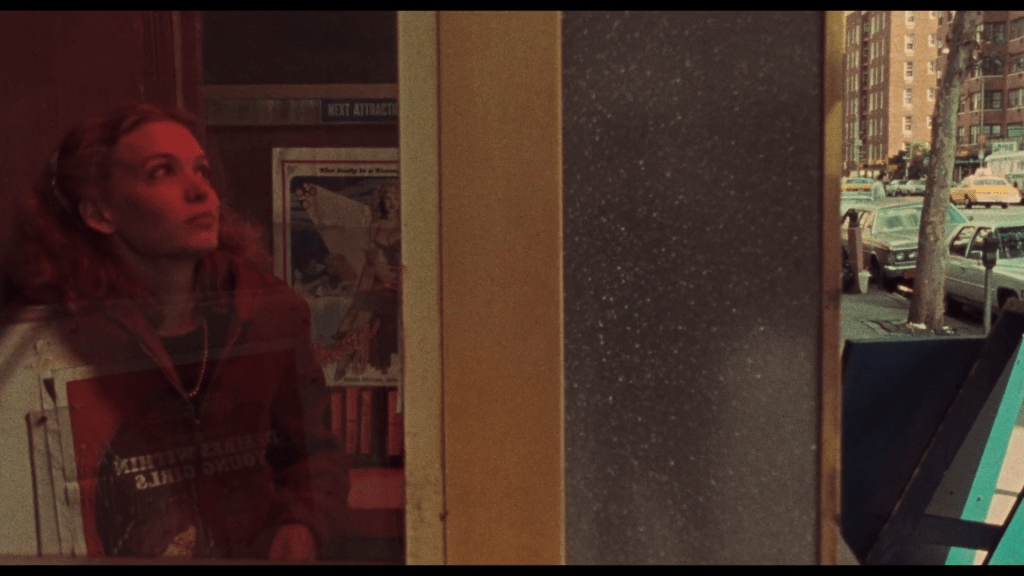

Of course, in Variety, I see a phantom of New York. Time had run out. It was the “real” New York for some generations and the imaginary for the later ones. I first read about the film when it was cited in Cahiers du cinéma‘s Summer 2019 issue, in which the magazine devoted a lengthy dossier to “les réalisatrices” — woman filmmakers. In his editorial, Stéphane Delorme wrote that Bette Gordon should have been the female equivalent of Jim Jarmusch by the time of Variety‘s release. I didn’t care much about the comparison, but, as usual, out of my respect and trust of the ex-editor-in-chief, I sought out to find myself a copy. As a film virtually unknown in my home country, I was surprised that it was not hard to find. (It is now available on MUBI and The Criterion Channel, in the latter, along with a comprehensive retrospective of Gordon’s other works.) I saw Variety for the first time, on a laptop, when I’ve just returned to New York for my second year at college, so a New York movie was always welcomed. To say the least, Variety, shot with its gritty 16mm stock featured some of the most beautiful images of New York City that ever graced the screen.

I was intrigued by the film immediately. The DVD copy didn’t exactly have the best image quality. At daylight, it brings the mundane a touch of haziness; at night, or dark spaces, a porno theater, a bar where photographer Nan Goldin bartended, the negative space that consumed in black and shadow shed each frame into something that could only be described as almost-mythical sensations. New York City of the 1980s bloomed in its trashy glory. Two months after my initial viewing, the Quad Cinema at 13th street hosted Gordon with the premiere of a new restoration. The image and sound were dazzling in its restored condition, with a memorable Q&A afterward. I didn’t remember the exact words of Gordon, but I remember the energy this radical filmmaker had brought, speaking like the provocateur she is. Of course, Variety theater no longer exists, but oddly, the space felt at home to me, for there’s serenity in Gordon’s images, which introduce the idea of a woman quietly subverting a place traditionally “for men.” This serenity then is synonymous with a true spirit of independence; it has a presence even when the film was at its most upsetting, namely, a series of erotic monologues from Christine. Unlike the on-screen boyfriend, we are totally at ease with the presence of Sandy McLeod, in the condensed space of a ticket booth, in the lobby of the dirty movie palace, in her tiny apartment, and soon we will follow her to all other places.

So then, this protagonist, a wanderer and a secret herself, becomes our guide towards a new sensation. Thanks to the pornography? I don’t know. But the question was: What if a woman enters a porno theater? The pornographic images yet are often absent, for Christine only needs to be in the lobby, hearing the sound, to understand everything. Not entirely, something must be hidden, and therefore one starts to discover. A Rivetteian conspiracy begins to unfold in the unconscious: What if the act of a handshake is redefined? What exactly is a “business,” and why is it important? What is going on in the fish market? What kind of machinery lies behind Louie’s “the car will be here at 6”? Why follow a man? But then, there is no Vertigo here. Although Gordon had effectively reverse-engineered the Scottie/Madeleine chase sequence into a woman’s obsession with a man’s mysterious or sinister routine, the intention behind it is deliciously blurred.

So then, I had foreseen its ending, a non-ending if you will. In stillness, a nocturnal street with only a dim light looming over the ground, and there comes John Lurie’s jazz score, I told myself: “This is the end.” And it turned out to be so. The story doesn’t reach any possible resolutions. Rarely does a film that is not traditionally structured end just as you wanted it to — they almost certainly start to drag out. But then that’s my problem. What I mean is that my sensibility matched that of the film. But there’s more.

The jazzy film is certainly anti-romantic when it comes to the distancing, but a pure sensation of curiosity is carefully preserved, connected to particular inner well-being and liberation. The emotion of eroticism exists solely at a precise midpoint between forces of the pornographic. There is the one that pretends to speak of love and pleasure, but only creates a machine, a simulator, a senseless object that is only a projected programming; and there is the scenery outside of the theater, the entire neighborhood which reigns on the pornographic one way or the other; and there is Christine who smokes alone in the lobby, hearing the sounds but not the images, where a spark of curiosity rises. Christine stands in between, where she will embark on her counterattack. In one way, she will recite, in a deadpan tone that recalls the works of Straub-Huillet, the objectified image and sound as pure texts, which immediately subverts, ridicules (the script was done by avant-garde novelist Kathy Acker); in the other way, serenity and true sensation emerge from such impureness. If Alain Badiou is correct, every film must go through “a struggle against the material’s impurity.” (Badiou) The answer here seems to be meditation and musicality. The yoga teacher’s voice, which our protagonist practiced, transmits its rhythmic melody back to the audience, who have come to sense the film’s true subjective. Look carefully, because for now, everything takes on a different meaning. What if there is a “plot” inside each handshake? What if there will be a murder in the fish market? Christine’s endless investigation towards Louie leads us into a framework where a man’s work is completely rendered as hollow shells, redundant gestures, and ultimately, without disclosures. There were no secrets to Louie: a man is a man, the business is the business. Louie disappeared into the adult video store, then mysteriously reemerged in the theater across the street, with everything in the middle buried in haze.

But for me, the central mystery was not it. Most significantly, this serenity of Gordon’s work lies in the shots, often in continuous takes throughout an entire scene, with very few cuts. Every cut then feels like waking up from a dream, only to fall directly into the next. The most simple and yet the most profound dream in the film: the one in Christine’s apartment, a “maid’s room” in the Parisian sense, where a medium shot sustained for around six minutes, simply filming the heroine’s movement inside her living space — but not exactly in the vein of naturalism, for it had gone way further than the everyday life. When the shot ended, refreshed through a decisive close-up, a sensation was born. This little intermission, which divided her somewhat awkward first encounters at the porno theater and the pending mysteries that shall follow, introduces us to a Christine at her most private and yet most secretive — all in this one medium shot, the most lengthy in the entire movie, like that of Michael Snow’s seminal 1967 film Wavelength, which uses its sustained duration and movement to slowly built up an inner mystery which no images or objectification can ever go to; and like the medium shots in Howard Hawks’ films, where the camera stripped all power, hierarchy and voyeurism from the image, and what remains is only the equality of difference, the only true and absolute eroticism — our curiosity: What comes next? What am I seeing?

Revised Edition, November 30th, 2021.

Thanks to Dr. Amresh Sinha

为 Variety – Clube Videodromo 发表评论 取消回复