by TWY

中文版:关于《双峰:回归》的28个碎片

SPOILERS AHEAD OF ALL TWIN PEAKS SEASONS, FILMS, AND MULHOLLAND DR. (2001)

LISTEN TO THE SOUNDS

“Listen to the sounds.” After we hear the line, Agent Cooper’s eyes direct toward the scratching clicking noise. Realizing this, the initial static shot of the phonograph then makes a propulsive motion forward. At this point, the phonograph was a black hole, and inside there seems to be infinite darkness. Yes, not only to listen to the sound but also to “see” the sound, that is the essence of the Fireman’s clue. Taking that line to kick off the return of Twin Peaks is not only a clue to Cooper (a clue that isn’t revealed until a full 16 hours later, in a shocking way), it’s also addressed to us, the viewers.

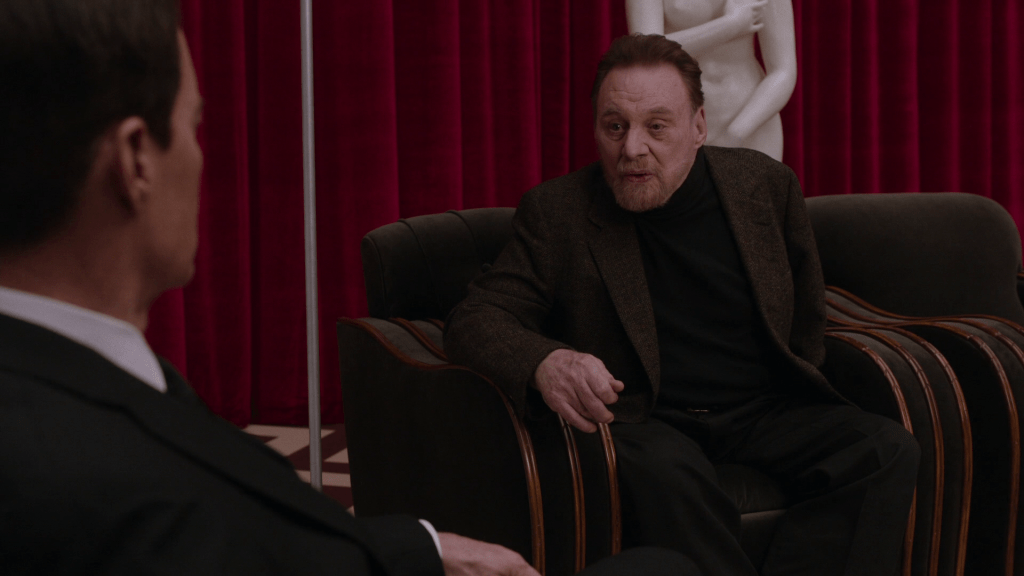

A great deal of theorizations have been done to the Fireman/Cooper scene, questions on its place, its chronology, and its significance to the role of Cooper had been explored. Right now, no definite answers existed yet. My personal interpretation doesn’t matter here, but whether the theories suggest the scene took place before or after the events of the series’ finale, when Cooper was led towards a darkening path, the only reasonable answer I could give (after reading some of such theories) was that, The Fireman’s clues are always more for us than for Cooper.

WEATHER REPORT

While the greatness of Twin Peaks is more than just its threads of stories, the whole range of feeling it provokes, from its dreamy small town atmosphere, its mystical score, its beauty of characters, etc., probably shouldn’t be expressed in words at this point, so better start with the narrative. Some oddities should be addressed first. In The Return, including its black-and-white first scene, which unveils Fireman and Cooper, there are plenty of segments like this – clues being told literally by the characters, the camera watches quietly, while the reverse shots reveal reactions from the opposite side, in short, long monologues of expositions. At this point, one wonders: Is this the “visual artist” Lynch we’re familiar with? Why suddenly start interpreting elements out of the blue, with the danger of being inertial or departing from the language of cinema?

But the point is, there are things one should know, and the author tells us with honesty. It’s important to understand that around 2017, Twin Peaks has become an oversaturated mystery box, after long catalysis since its last chapter premiered in 1992, with fans madly enthralled with every element of the story, with 25 years time worths of texts, criticisms, theories, and speculations piled high. Thus, for their own sake, Lynch and Frost must, from time to time in The Return, share with the audience that is necessary to keep it alive, an opportunity to gain an equal relationship with the audience and, more importantly, to freeing themselves from existing secrets in order to generate more – to become the “goose that lays golden eggs” that Lynch envisioned back in the day. The premise that drives Lynch’s visual genius is curiosity, which is what all the “hints” and “clues” offer. These clues are clear enough to serve as a beacon of light, but not as exaggerated as to counteract the mysteries, it lies within the right balance between straightforward, purely cryptic and nonsensical, where our curiosity is endless. We are not only armed with clues, but also have the space to imagine.

Those gestures in Twin Peaks are always placed somewhere between pure information transfers and cryptic whispers. Might as well use another Lynchian hobby for comparison – weather reporting. In the years around the days of INLAND EMPIRE (2006), and more recently during this coronavirus era, Lynch posts daily updated weather reports on his own website (which no longer exists, now through YouTube): under a fixed angle, Lynch broadcasts the day’s weather in Los Angeles in his trademark accent. Behind his workbench is a window that just happens to be out of the frame, which Lynch uses to observe the color of skies while reporting. We can’t see the sight outside the window, but Lynch’s speech leads us to believe: the clear sky delights him, and his wording becomes ecstatic (“Beautiful – Blue – Skies! Golden Sunshine!“). Even in the occasional rainy or foggy days, one still hears the longing for sunshine in his tone of voice.

Isn’t this kind of weather reporting spirit what the expositions in Twin Peaks all about? He tells it with passion, shares what he enjoys, and leaves the rest to our imagination. And the ones we’re not supposed to know, we’ll never know (“Frank, you don’t ever want to know about that.” “We’re not gonna talk about Judy.”) It’s not just messaging of information, it’s a gesture of cinema. Godard leads us the way, by saying: “Television makes forgetting, the cinema creates memories.” Twin Peaks has its own weatherman: in the first episode of Season 2, the mysterious Major Briggs, astrophysicist, tells his rebellious son Bobby about his dream in which the latter becomes a happy man in the future. This is one of the most memorable moments of that season, but we’re just sitting in that one booth of the Double R diner, watching the two actors, who had very different styles that were nothing like father and son, recounting these stories in plain monologue. Don S. Davis portrayed the Major with a subdued tone, who remained soldierly serious even when describing such a spectacle, yet the delivery was unlike that of a report, but of sincere sharing; meanwhile, Dana Ashbrook, who plays Bobby, retains his exaggerated, soap-opera expression, like his hilarious bark in the Pilot – unlike Davis, this is not an actor who can keep his emotions hidden, any touch or shock he feels will be written immediately all over.

Such delicate expositions may not sound so “visual,” but that is why the emotional energy is amplified when we actually receive sudden bursts of pure image and sound. If the explosive experimental imagery in Part 8 had been just a series of eerie images, it wouldn’t have held the emotional power it now possesses; if the Mitchum brothers hadn’t mysteriously discussed the cherry pie in the box, the great moment that belonged to “Dougie Jones” wouldn’t have been so fulfilling; and back in the beginning, if The Fireman hadn’t given Cooper these seemingly random hints, we wouldn’t have been so deeply disturbed when we reach the finale.

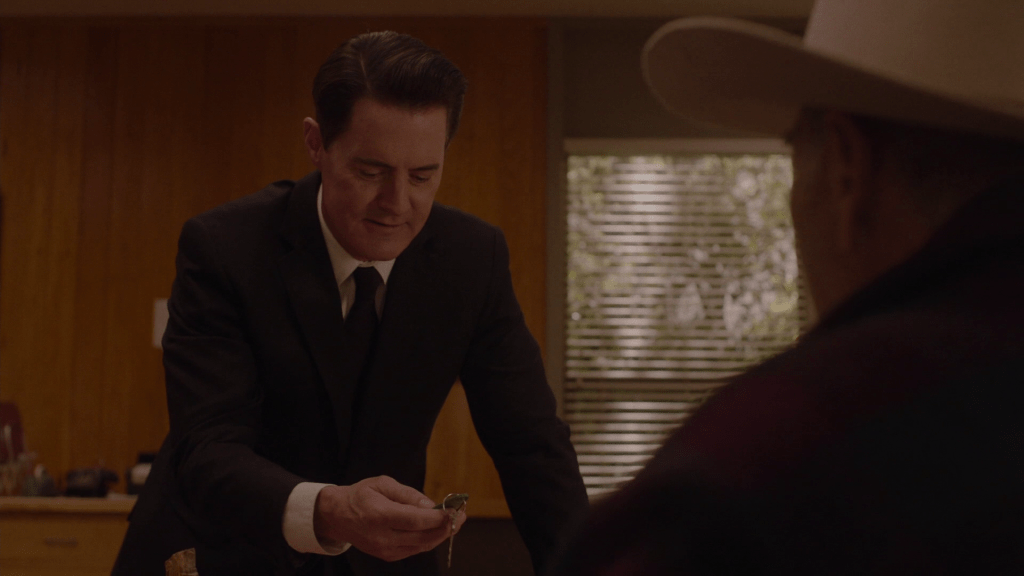

25 years later, the Major’s prophecy came true, when Bobby, now a police deputy, tearfully blushed at the classic Laura portrait (Part 4), bringing back all memories of Twin Peaks – this is also the first time Laura Palmer’s theme by Angelo Badalamenti is heard in the entire return season. Pay attention to the sound (and its absence). Gorgeously returning, FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper requests the key to Room 315 of the Great Northern Hotel from a puzzled Sheriff Frank Truman (Robert Foster) in Part 17: “Major Briggs told me that Sheriff Truman will have it.” Davis, who died in 2008, returned for the season only in a bizarre form — spirit and intellect separated from his body, with no apparent visual evidence to back up his prophecies. Yet when Cooper said this to the sheriff, yes, we believed him unconditionally, this great weather reporter.

FILM SCHOOL

It’s been three years since Twin Peaks returned to television, meanwhile, three years since I’ve entered film school. For me, it is the 21st-century film school, an 18-hour treasure. It’s not just about the experimental, the haunting, the so-called “Lynchian” moments (deliberately imitating those imageries, which is always interesting, have proven to be harmful instead), but it’s about its master class in rhythm; its teaching on how to spend screen time, how to pique curiosity (the secret of “2”), and how to use the three basic camera set-ups of cinema (in other words, what’s a shot-reverse-shot?) It teaches you how to create energy from sound, with rich dynamics of emotion and the bursting/absence of music. Also, how to live in the moment, meanwhile thinking of the future and the past… At the same time, it is also a masterpiece of comedy.

TV OR CINEMA

“By ranking two series at the top of our top of the decade, we are dividing things between, on the one hand, films and series that still speak the language of cinema (who know what mise en scène, editing, shot, realism, acting, etc. are……) and on the other hand, films and series that do storytelling, providing the viewers/users with ‘content’, ‘universe’ and ‘information.’” (Stéphane Delorme, Cahiers du cinéma, No. 761)

TRAIN

Somewhere during Part 2 of The Return, the static camera depicts a train crossing a night road. The railroad brought us back to the origins of cinema, of Lumière, of suspense. The moment the road pole is lowered, suspense emerges, and we wait for the train to arrive. Soon the sound of a train comes from outside of the picture, anticipation rises, the sound gets louder and louder, then the train whizzes by, suspense lifted, but what’s next? For those of us just getting into the new season, this wait is also for Cooper, for Audrey Horne, Shelly Johnson, Sheriff Truman, and for all the familiar faces and places we expect this train to bring to the screen. Perhaps an over-interpretation, but the train shot, wordless, seems to have already unveiled the true meaning behind all the waitings.

EMPTY HOUSE

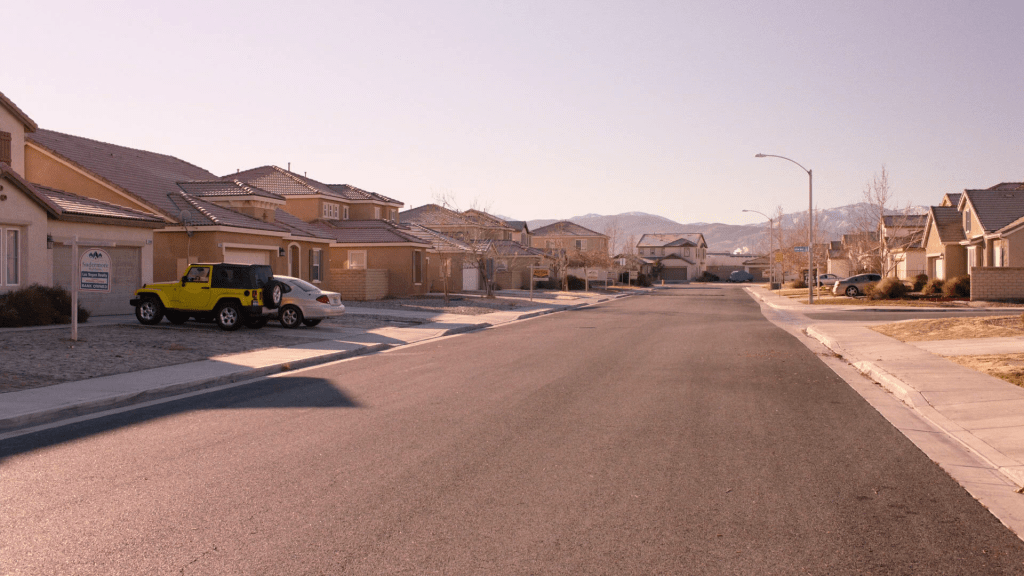

According to a 2017 interview with Lynch in Cahiers du cinéma, Las Vegas was Mark Frost’s idea: it was he who envisioned Dale Cooper suddenly appearing in an empty unfurnished house in the city 25 years later (an idea that eventually appeared in Part 3). The subprime crisis of 2008 served as a backdrop, as many “ghost town” properties appeared in the flat desert city when nobody can afford housing – creating a bizarre and ironic sight (while the actual shooting location is not in Les Vegas but in California, the sale signs and the desolation is absolutely real), with the additional humor added by Dougie’s appearance. Why come here? It may seem random, but it’s also a kind of karma. If the original Twin Peaks in the 1990s grew out of Lynch and Frost’s mutual interest in the mystical female tragedy like that of Marilyn Monroe, we can say that this new idea of Frost was sufficient enough to match Lynch’s frequencies. The idea of an empty house also provides spatially imaginative and intriguing image, just as the Francis Bacon-Inspired New York glass box in Part 1 is clearly a product of Lynch. And now we have two seemingly empty spaces, like two blank canvases, waiting for the brush to stroke on. It was this rare resonance of inspiration that sparked the return of Twin Peaks, a series that was the product of their collaboration from the beginning, and in that sense, this tacit understanding was all the more necessary. So, where was the essence of Twin Peaks for both authors in the 2010s?

ANTI-NOSTALGIA

As many viewers had realized in the opening parts of The Return, the new Twin Peaks doesn’t seem to seek to focus its “narrative” on the town of Twin Peaks, nor does it rush to introduce old characters and places that audience are dying to revisit, and is therefore seen by some as a piece of unrelated work in the name of the old show. But just like the show’s 25-year-long “winter break,” after such a long hiatus, this return season is in itself about getting back. Some say The Return is a work that calls for resistance to nostalgic remakes, but we may not even have to rise to the level of resistance at all. There are nostalgia in Twin Peaks from the beginning. But the key to the matter is, are we really that close to Twin Peaks? At least our authors weren’t, and after watching The Return, it’s hard to imagine a supposedly “normal” return trajectory: perhaps another dead girl in Twin Peaks, perhaps another killer, perhaps another visit from an FBI agent. After the great reaction of Season 1 and the radical supernatural evolution of Season 2, we’ve already seen such “remakes” in the second half of the second season, as well as in the film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Fire, where the former proved to be self-parodic, eventually sank into unbridled cheap humor and ridiculed a host of classic characters; and in the latter, the lone helmer Lynch consciously designed the first act – the murder of Teresa Banks and Deer Meadow as an anti-Twin Peaks experiment, deconstructing the elements that define Twin Peaks‘ appeal in negative viewpoint: the diner, the sheriff station, the FBI agents, the murdered mystery girl, etc.

Twin Peaks: The Return, on the other hand, shows a whole new kind of possibility: a series that attempts to return, looking for the possibility of a real return as its stories evolve and recur, characters appear and disappear. That’s why, in the beginning, all the elements in the narrative were fractured to all corners of America.

NEW YORK CITY

The Return‘s most intriguing plot in Part 1 was the New York City glass box story, mysterious and inexplicable, and not particularly in the style of “Twin Peaks”. I’m sure many people can vividly recall the unparalleled reaction on the day of the premiere to seeing the three words “New York City” on the screen as they suddenly appeared in the night of Manhattan. We later learned that the two beautiful drone shots themselves were even just online stock footage! Why was there so much magic? Let’s first go back to how the opening segments of Part 1 were constructed.

First, Lynch shows us the familiarized. He prefaces the opening credits by recalling images and sounds from the Pilot episode and Season 2’s final episode: Laura Palmer telling Cooper, “I’ll see you again in 25 years”; the empty shot of Twin Peaks High School corridor when Laura’s death was announced; the very short shot of the unknown girl screaming out the window, only this time Lynch chooses to slow it down as if playing back as memory, our memory of the show; and the opening title “TWIN PEAKS” was accompanied by the classic portrait of Laura, reminding us what the heart of the series has always been.

So far, we are in the familiar. Then, after a brand new opening title (at which point we get a glimpse of the upgraded texture of the Red Room), in a black and white image, a graceful and somewhat erratic shot tilts up, and we see The Fireman, then cut to Cooper seated opposite. While this passage has clearly been detached from the original series in terms of visual style, we can still say it’s familiar – after all, who wouldn’t want to quickly see the return of such great characters? Immediately following this segment is the comeback of Dr. Jacoby in the woods. Why him of all people? We ask ourselves. It’s not how one usually introduces returning characters. Here, the camera design is completely detached, no close-ups, no iconic music, and we don’t quite understand Doc’s purpose by ordering these shovels. The entire scene unfolds in real-time, with the camera silently observed from a distance, and the gaze behind the tree even hints a surveillance perspective. But even so, we’re in Twin Peaks, we saw familiar characters in familiar landscape, and even without the story, everything seems to be soothing, therefore, we put down our guards. But then…… You knew the rest.

Connecting Dr. Jacoby’s appearance to the New York Glass Box scene is a brief blackout that fades in and out, a technique Lynch and editor Duwayne Dunham will be using throughout the 18 parts. A kind of theatricality can be sensed, like the red curtain, and when the curtain comes down, we are caught in mystery because we don’t know what will fill the stage when the curtain lifts again. This is a similar to another Lynch language — the slow dolly-in shots (represented in The Return, most iconically, by the atomic bomb shot): the camera focuses on somewhere, and with it, moves into a dark corner, accompanied by the sound of a breeze. At this point, the viewer asks himself: what’s on the other side of the world after the camera comes through? Sometimes what greets us is a completed otherworld (Eraserhead), and other times, the other side looks like nothing, but everything has changed (Mulholland Drive). It’s also naturally a challenge to continuity filmmaking and continuity of thought, ensuring that we remain highly focused at all times – it’s not a straight path, it’s a constant jump through the non-linear space-time, wormholes in Lynch’s work (isn’t it strange, there are actual wormholes in this season!), they’re both shortcuts and deep, dark paths.

THE RED ROOM

The Red Room is perhaps the most iconic Lynch stage, a synthesis of all the inspirations mentioned above condensed into one: a confined space, but with infinite possibilities. 25 years ago, Cooper walked through it, the audience was in sync with him, and no one knew what would appear in the next room, especially when they looked exactly alike. The shock of seeing it again is unmistakable: it is too familiar, yet far from intimate. We enter a state of chaos between the knowing and the unknowing: we sense variations of the material, no longer a translucent bright red, but a thick, opaque dark velvet red. At the same time, the high definition of the digital photography shatters the dreaminess of the film, every detail becomes clear and sharp, even the 16:9 HD ratio makes the view more unsettling as if the room changes spatially according to the size of its canvas (something already evident in Fire Walk With Me).

The naming of the Red Room was controversial again, with the dancing Man From Another Place calling it the “waiting room” in Season 2, and most of the time we call it the “Black Lodge,” but are we just looking at the dark stripes on the floor at the expense of the lighter half? At the end of Fire Walk With Me, Laura weeps with joy with a version of Dale Cooper, basking in the divine light of angel in the Red Room (an image that used to be the ultimate image of the Twin Peaks world until The Return), and when that happens, isn’t the Red Room also the White Lodge? At the same time, again, we can’t be certain that the room above the convenience store is an entirely evil place, where Cooper’s Double was able to imprison Diane (as Naido). When Laura walks through there from a painting in Fire Walk With Me, she understood herself better and saw into the future, and when the returned Agent Cooper and MIKE came here, it is again for a different mission, with the vanishing agent, David Bowie’s Philip Jeffries also in the neutral, simply a seasoned guide of space-time travel. Meanwhile, I don’t think the Fireman’s house on the purple sea is the so-called “White Lodge” either. It is true the Fireman can generate the sacred Laura orb here (The Return‘s most emotional scene, in Part 8), but when Cooper falls into somewhere in Part 3 and sees Naido, the imprisoned Diane, he also discovers the ocean on the balcony. Are the two locations interconnected? Perhaps naming and defining itself leads towards dead ends, or rather, towards infinite changes. As Hawk cautiously explains the Fire, “it depends, depends on the intention behind the fire.”

AUDIENCE

There are few shows or films those responses involve the word “audience” as much as the three renditions of Twin Peaks: the original series, Fire Walk With Me, and now The Return. Ultimately, one must examine the attributes it initially held as a serial. As a public network show, the shooting type of the original series indicated that it was almost impossible not to be hijacked by the ever-increasing demands from audience. “Who Killed Laura Palmer?” This question is an inescapable haze, for television’s nature is informational, the more information the merrier. Twin Peaks is the dispatch from cinema that tries to conquer this land of information. But then that was the end: then-ABC president Bob Iger pressured Lynch and Frost to reveal the real killer, who, as Lynch put it, was “slaughtering a goose that lays golden eggs.” This battle for creative power proved to had bear unintended fruit in its aftermath: Lynch’s revelation of the killer in Episode 14 (Season 2, Episode 7) proved to be one of Twin Peaks‘ most iconic episodes, with its stunning ending sequence intercutting between “brutal fucking murder” of Maddy Ferguson and Julie Cruise’s melancholy hallucinogenic songs, bringing emotional closure to the entire Laura Palmer mystery; Fire Walk With Me then allowed Lynch to dive within, back to the central character of Laura without the pressure of mysteries, and the negative reviews at the time of release did not prevent people from recognizing it now as his most humane and intense film, a masterpiece that launched a new phase in Lynch’s cinematic style; of course, without this series of twists, The Return would not have been possible 25 years later. Overall, the audience, as a central element to the world of Twin Peaks, has always filled its world with an extra layer of suspense from outside the telly box.

Twin Peaks: The Return doesn’t choose to follow the path of the original series. It is a complete, standalone project, with Lynch and Frost entirely at the helm, it still perfectly recreates the kind of off-screen audience-generated suspense from 25 years ago, which is why Showtime’s weekly distribution was better suited to the show than the binge-watching model of Netflix. Is The Return merely teasing audiences in the name of a remake, or is it a genuine gift? As mentioned above, I must reiterate that this is Lynch’s most generous work to-date, a stunning magnum opus, precisely because it chooses a more dangerous path, and invites the viewer to take the road with the two authors on their “attempt” to return to Twin Peaks.

PALMER’S HOME

Initiated back in 2012, Lynch and Frost then spent a year building the script for the first two parts of The Return, and here, a circle forms as Cooper, in the end of Part 2, dropped into the horrible glass box back in Part 1. It seems that this epitomizes the entire structure of the series, an ever-overlapping cycle that will be fully reached in the final two episodes. The end of these loops is even the same, the Palmer house, the infamous No. 708. In Fire Walk With Me, we witness the pain and suffering of Laura’s family, and 25 years later, the only one who remains in the house is Sarah Palmer. This scene is something we’ve never seen in Lynch’s previous work: a completely private moment. The stilled medium shots, and those silent, mundane images, not unlike Jeanne Dielman, the story of motherhood, and Sarah was once a mother. Grace Zabriskie’s silent gaze is as disturbing as her screams. The image we see of Sarah this time is almost identical to the composition of the last time Laura says goodnight to her in Fire Walk With Me, except this time, we don’t see the portrait of Laura that happens to be just outside the left side of the frame (an object still important this season). She had not come out of this shadow, she never will, and all were presented here in her silence, in the hisses of the television beasts.

But you may ask, why the sudden choice to cut here? For one second, we were seeing Cooper drifting down in space, accelerating, not knowing where he’s going; and in the next, Sarah is sitting in the darkened living room watching animals slaughtering one another. Lynch’s stiff transitions in the editing sometimes seem to be nonsensical, and at first glance, it does feel puzzling, but by connecting the dots as the episodes progress, a terrible truth develops. 1. Sarah has apparently been taken over by supernatural forces (Part 14); 2. the glass box is confirmed to be Bad Cooper’s creation (Part 10); 3. when Bad Cooper finds the coordinates he wants, the vortex was originally going to teleport him to the Palmer House (Part 17). Therefore, one can assume Lynch/Frost’s thinking: Cooper was set up by the Red Room and entered the trap (glass box) set by Bad Cooper, which he should have been transported to Palmer’s house to face the evilest “Judy” (at this time Sarah needed the violent TV show to get “Garmonbozia,” the evil energy in the Twin Peaks canon, visually in the form of cream corn, symbolizing the pain and sorrow in the world). Naturally, Lynch couldn’t spoil everyone all at once in this early act, but this little ambush, subtle, was a hell of a scare upon realization.

SPACE

Outside the town of Twin Peaks, Lynch and Frost bloomed with inspiration: Las Vegas, South Dakota, Montana, Philadelphia, New York, New Mexico, even Argentina, Paris, and the Pentagon… A series of stories and fantasies take place there, with FBI agents poking around in private aircraft, Bad Cooper driving his macho truck alongside electricity, looking for “coordinates”, and Lynch as director, piecing together clues with the hands of editing..…. While in Twin Peaks, everything we see seems to come to a standstill, with characters trapped in their own space for extended periods of time (Ben Horne, Audrey, Lucy who can’t understand cell phones, Norma who guards at the Double R forever), or lost somewhere (Jerry), or experiencing various painful oddities (Bobby witnesses gun violence, followed by piercing sounds surrounding a vomiting girl; bad cop Chad and the Drunk; drug still dominates the town’s underworld economy; domestic abuse and sexual assaults everywhere; plus, Richard Horne’s evil deeds).

CINEMA

Confronted with the shifting spaces of this work, the audience often attempts to make sense of it based on a logic that seeks to mimic the physical world, but ultimately, we are watching a work created entirely by cinematographic ideas: without its superimpositions, backward-playing and jump cuts, how do we see and experience Cooper’s journey in the Red Room, where we dwelling in the intersection between finiteness and infiniteness? In The Return, quite a lot of time is spent with characters simply driving through the night, either walking towards a porch, or standing somewhere waiting, or crossing into another world in flickering jump cuts. The gigantic closeup of Cooper is superimposed on the victorious sheriff station reunion, and his slowed, low voice says, “We live inside a dream.” The dream can only be that of cinema, a dream carried with purely cinematographic ideas, something that also transcends the dream logic of Mulholland Drive, which was implied by Lynch using a point-of-view shot that pushes into a pillow.

The Return is a work that devoid Freudian indication of dreams, where purely cinematic gestures take command. With Part 8, we see a movie screen inside The Fireman’s mansion, where he receive images of mankind’s evil terror, and because of that, he release the golden seed into the screen, and into our world; and he (and Lynch) gets to manipulate with teleportation (editing), resulting in characters flickering in or out of the screen, or being totally erased from the film. With the constant, repeating gesture of rewinding and forwarding in Part 3, the speeding-up and slowing-down inform the danger in electricity; in the same episode, one opens a skylight, and suddenly climbs into the vast universe that surrounds us, as if something out of Maya Deren’s At Land, where match-action cuts teleport its character through infinite numbers of spaces, running and crawling. When the series must reconcile the loss of certain actors (Don S. Davis’s Major Briggs, Frank Silva’s BOB, young Laura’s portrait, etc.), Lynch places footage of them from earlier seasons directly, dispatches them as phantoms from the past, watching over…… In Part 10, Gordon in 2017 opens his door, and he sees an image of a 1992 Laura, calling for friendship, superimposed in front of him; a few episodes later, he will also see his own archived image within the recalling of his dream, and only then will he remember the information Agent Jeffries once warned him about. Both images are from Fire Walk With Me. Such extractions were seemingly abrupt moves to put on the narrative, but soon they were revealed to be subtle indications. When Cooper arrives at his own destiny, it is at the end of this prequel film that he descends – where newly shot footage and the film from 25 years ago (made black-and-white) intercuts between, and the film’s existence allows him to make a dangerous move that changes history. In one of the most beautiful sequences of the season, Bad Cooper and a Woodsman slowly walk up the stairs leading to the place above the convenience store, where their images flicker out in jump cuts with the sound of electricity, and the film slowly dissolves into a propulsive shot of the deep, dark woods – a totally impressionistic move. It’s the shot’s slow advance in exquisite sound that sends us to the supernatural realm on the other side; and when Bad Cooper walks to the end of the room and opens the door, the sound suddenly becomes naturalized, and what he sees when he opens the door appears to be nothing more than a night time motel… What is supernatural? Perhaps it is something that just hides in a seemingly ordinary space.

THE ROADHOUSE

The Roadhouse usually appears at the end, not here though. Of all the Twin Peaks locations this season, this charming bar, surprisingly, becomes the most bizarre, as it appears to be a place that embraces all that is wonderful about this strange world. And indeed it is sometimes. This is where the audience gathers, where they dance on the dance floor to the band of the hour, like the audience in front of the TV screen. No matter how much we accept or reject the fragmented scenes of the show, we will always be willing to throw ourselves here unconditionally, because this is the symbol of that classic Twin Peaks. Whether it’s the dream-pop of Julie Cruise or even the heavy metal from “The” Nine Inch Nails, people want to be here (the most “infuriating” Audrey scenes in The Return revolve entirely around the idea of “going to the Roadhouse”), and this is also where we briefly part ways with all the stories in half of the episodes. But at the same time, the location resists the temptation to mere musical pleasure (and closure), instead it conjures out some of the show’s most bizarre and random acts.

The 2-part premiere closes with Chromatics’ unrelentingly celebrated “Shadow,” which begins a new tradition in the world of Twin Peaks: we see familiar characters and familiar music, but everything is recreated in a modern way: the symbol of a perfect sequel. The two subsequent episodes ended in similar way, also with light choices of songs. Since then, we’ve come to expect the bar in every episode, and sometimes feel melancholic because seeing it often indicates the end of one episode as well. Lynch and Frost have always been masters in cultivating these little habits inside the audience. But needless to say, they are also the best at breaking those habits, which is the generosity and secret of the series. We always come with expectations, the author often lives up to them, but everything doesn’t always unfold according to the plans.

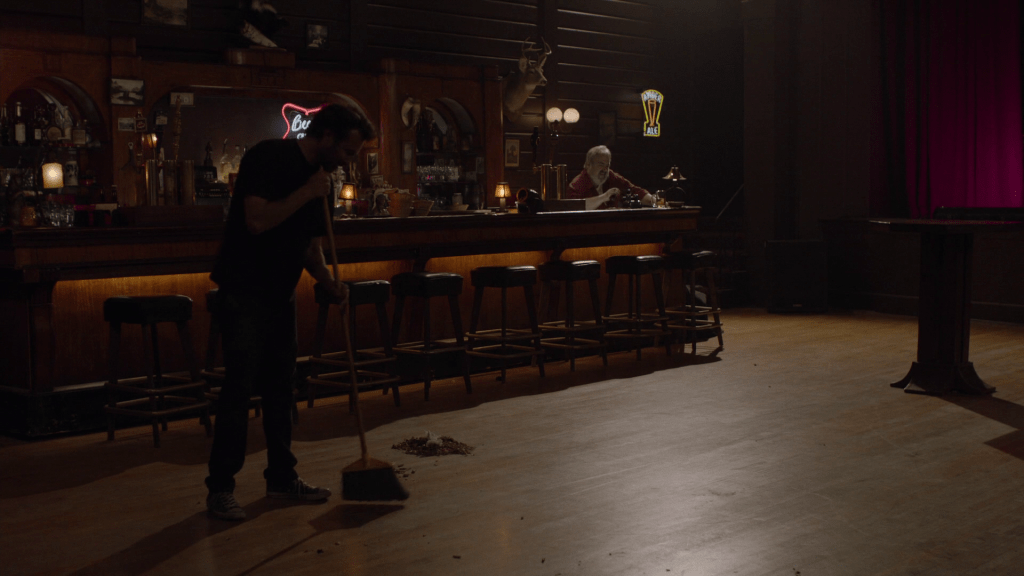

However, while enjoying the music and feasting on these beautiful moments, perhaps it should not be forgotten that the owner of the Roadhouse in the show, for more than half a century, has been the Renault family. To highlight this, Lynch and Frost went out of their way to bring back Walter Olkewicz, who played the now-decreased Jacques Renault from the original series, to play a new Renault member to run the bar. As one of the key players involved in Laura’s murder, you’ll remember how Frost aimed his camera at Jacques’ lips and filmed his sickening words in his only directorial contribution (Finale of Season 1). In The Return, his words and deeds are no better (see the notorious sweeping scene in Part 7), and we understand that Renault family’s prostitution ring is still in existence, and Lynch brings back the character whose secret reminds us of how Laura was plunged into the dark side of the world, leading towards her death.

So the comforts of the Roadhouse are destined to be ephemeral as well as infinitely variable as the music genre change between different episodes. It could be very bold to claim that in The Return, the Red Room dynamic of “finiteness/infiniteness” has been extended to every corner of the Twin Peaks world, even in Cooper’s eyes, “it” can be activated at any time (the one-armed man MIKE in the Red Room flashes into the scene with a translucent layer; and in Part 18, the room pulls Cooper back immediately after Laura disappeared). When the real killer of Laura was revealed back in Season 2, in a Lynch-directed episode, it was also the people in the bar who first sensed the tragedy: “it is happening again.” But in The Return, the Roadhouse features a different sensory, which is embodied in random characters sitting in booths, as if in an existence that suspects parallel space-time. Using Part 8 as the dividing line, starting in Part 9, these random characters begin to pop up in the bar, and they (mostly women) appear only once, and will never be mentioned again after. Just as you never know what you’ll encounter the next time when the curtain is lifted in the Red Room, so as the sense of unease given to these random encounters in the Roadhouse and their stories: soap opera plots, occasional dangerous intrusions, the ubiquitous violence, and the occasional flash of a clue about some “main” plot character.

The audience’s first reaction to these characters was as disturbing as it was watching Lynch’s return to directing the season two finale for the first time. We are presented by the authors with people who have nothing to do with the “main” plot, and then we enter a state of puzzlement, even anger, some even protested: why were these precious screen time not given to the more “important” characters? Such confusion culminates at the end of Part 12, when Audrey finally returns, but only stranded in an extended scene of great anxiety and confrontations, spitting out names of people all over. But Lynch and Frost’s portrayal of the Twin Peaks space in this season is devoid of any so-called hierarchy of “important” or “unimportant”: except for the two more stationary elements: Twin Peaks Sheriff’s Department and the Roadhouse, any other scenes are thrown around in a more or less irrational manner. This line of thinking is indeed confusing, but on the other hand, it is more of equality. The Return is perhaps one of the few works I’ve seen that takes every scene in such rigorous control, even when it feels random. Once a scene is introduced, a complete command of its rhythm, language, sound, and camerawork is immediately established, and each scene seems to work as a standalone short film, placed in the infinite container that is Twin Peaks. Never a “filler,” a television term, an informational term.

The appearance of Kyle MacLachlan’s name at the end of each part indicates the end of the episode, but Cooper, in whatever forms, sometimes doesn’t appear with substantial screen time in all episodes, and in a few episodes he appears for even less than a minute! Only the craziest of filmmakers would dare to make such a decision. But I wasn’t ready to talk about Cooper. After all, this is an infinite container, so I might just peer into some of those infinities. Are the characters at the Roadhouse really so “random”? Audrey and Charlie’s name-calling game is a headache, isn’t it? The fact is that Lynch and Frost had hinted at it early on, and it also serves a precautionary note that leads to the show’s ultimate moment, Part 18. Furthermore, this dangerous and subtle allusion leads to another path, to the real world, to these “random” hints that we, everyone, are part of this world, and the stories will happen to anyone.

“WHAT IS YOUR NAME?”

Back to Part 1, at which time we don’t know much about the setting of The Return, but aren’t the glass box sequences in New York City, and Sam and Tracy, some of the most iconic “random” moments in the show? As the ones in the bar that quickly disappeared from the grand narrative, so did this couple after being brutally murdered by the “Experiment Model.” More obviously, just before a particular pivotal moment, Lynch and Frost decided to put in a curiously comical scene. Yes, at that time, we were just curious, not yet infuriated.

A woman named Majorie Green (Melissa Bailey, who played the neighbor who was mistakenly injured by the unlucky gunman on Mulholland Drive, apparently rented the wrong apartment again) walks down the apartment aisle with a Chihuahua (homage to the Gordon Cole joke in season two). The keys dangling from the woman’s arm makes all sorts of clanging noises, the key to this scene (pun intended). The funny thing is that it took us the next five minutes and at least four characters to find it, in just a few minutes we hear a litany of names: Barney, Ruth, Hank, Harvey, Chip… except for Hank, all of whom appear only in dialogues (along with one bodiless dead person), and Chip, who ain’t got no phone. It’s clear that such a scene is an elaborate prank and foreshadowing because almost all of the above names will disappear in the episode afterward.

Although we don’t hear the names above again much in the dozen or so hours that follow, a string of new names come to mind one after another: Richard, Linda, Red, Billy, Bing (Riley Lynch’s character who yells in the diner, “Anybody seen Billy?”), Trick, Chuck, Tina, Carrie Page, Alice Tremond…… The identity politic of names and objects in the show is both a toxin and a blessing, because perhaps only in the world of Twin Peaks can a few simple names cause such an effect, and precisely because this world has contained so many hallmarks, yet its authors are so determined about deviating from audience’s expectations. Lynch and Frost lead us, discovering a curiosity we never had before. Perhaps it is in the over-interpretations and theorizations that Lynch himself most resisted, we instead find the magic of the show for the audience.

Together, Lynch and Frost had written over 280 characters, large and small, some silent and others wordily, throughout the eighteen-part journey, with 39 returning actors from the original series, and the two creators never take sides. Taking the first part again, for example, the plot of two new storylines, Sam and Tracy in New York and Bill Hastings in Buckhorn, takes up almost all of the first episode, with Lynch presenting these two in the highest degree of concentration, but then with great fluidity, he has the old characters intertwines in-between: Ben, Jerry, Lucy, The Log Lady, Hawk, Dr. Jacoby……, in seemingly cameo appearances for just a few minutes. The creators return to the audience what they know. As Cahiers praises in its dossier: only a quick glance is needed, just enough to understand that they are still here. The effortless treatment of classic characters seems to give the impression that the series was never off the air in those 25 years. Therefore fanfares are not needed (only the Coopers, the Dianes and the Lauras get that courtesy, as these characters are unquestionably central to the world, and most related to the delicate dialectic of nostalgia/anti-nostalgia), and we just need to get right into where they reside in. This highly equalized relationship of the characters ensures that the audience will be prepared for any possibilities as we move to the most critical final stage, while gradually expanding the world of Twin Peaks to the edge of its frontier, and partially satisfying the audience’s desire for continuation and closure.

In the final part of The Return, Cooper (or “Richard”?) asks two questions, “What is your name?” And “What year is this?” They become the core existential questions in the show as to “Who am I and why am I here?” Not coincidentally at all, these are also questions we often ask throughout the series. Aside from names that are tossed around, the chronology in which the series takes place is also a mystery – apart from 1945 and 1956, which are explicitly stated in Part 8 (clearer interpretations they are, more powerful the unknown implies on the other), we don’t get indications of what year the series takes place, and such mystery peaks in the finale, a combination of reminiscences of all the past confusions that leads to this moment. The question about time will come back. When Cooper descends on the purple house in Part 3, the jarring jump cuts, revolving in electric crackling, dazzle us, at which point Cooper asks, “Where is this? Where are we?” At this point, the audience shares these mysteries with the main characters, as Lynch always says: each of us is a detective. Where Lynch and Frost’s generosity lies is in their acceptance of such questions because for everything the audience is asking, the series is asking itself too.

FREDDIE

Let’s focus on one, perhaps the most “random” character in the entirety of The Return: Freddie Sykes, the British young man with a green super glove. An idea of Lynch, and Jake Wardle was casted because Lynch was fond of his multi-country accent impersonations on YouTube (released in 2010 and currently has over 32 million views). Of all these new characters in the return season, Lynch also seems to be partial to him, even giving him one of the most “sacred” mission in the finale.

FREDDIE & ANDY

Just as Lynch chose him for his linguistic talents, so too does The Fireman, who, in his all-seeing-and-knowing perspective, invited him, an outsider, to Twin Peaks. This story was told by Freddie to the “elder” James Hurley in Part 14 (an episode where telling story as a gesture is almost singled out as a structural theme, along with Gordon telling his Monica Bellucci dream, Albert telling the origin of the “Blue Rose”, Bobby’s family tall tales, and Lucy’s brief tale on going to Bora Bora, which confused Gordon). In the first half of the same episode, The Fireman also unexpectedly recruited another person, Deputy Andy. As Freddie asks The Fireman, “Why me?“, in which he replied, “Why not you?” Freddie’s story, which follows the four police officers’ adventures to the Major’s “Jack Rabbit’s Palace”, is not only an elegant metamorphosis in cinematic form, but can also be called a commentary on Andy’s earlier triumph.

As a classic character, Andy’s “status” in the original show was clearly “not very high” in front of the “senior” roles of Cooper, Leland Palmer, Sheriff Truman, Ben Horne, and Albert Rosenfield, as he didn’t look “manly” at all. For many episodes of the second season, he was imprisoned by the writers in a love triangle between Dick and Lucy, playing ridiculous comedic routines until the real creators returned at the end, rescued him and let him be the guide to Cooper towards finding the Black Lodge. Lynch and Frost have always been fond of him, and even gave him a memorable yet surreal scene at the beginning of the Pilot: his sudden, painful, yet silly cry in the presence of Laura’s dead body, even though the two of them never knew each other – it’s just who Andy is. Our two creators never doubted the innocent wisdom of this seemingly naive and silly police officer, which led to his transcendence in Part 14. Andy’s arc was “a straight story,” but a story to greatness nonetheless. Looking back at the scene where Andy ascends, surprising at first glance, but the answer was clear from Lynch’s staging: after seeing Naido, all that was given to the other three deputies were stilled standing positions, only Andy crouched down to tightly hold Naido’s hand, while his eyes peering into the vortex in the sky, as if expecting something.

Corrupt cop Chad says with contempt in Part 17, “Isn’t that the great, good cop deputy Andy?” Yes, this cynic soon took a hit from Freddie, and his story came to a screeching halt. Freddie and Andy’s unexpected victory is a kind of anti-macho statement, just as Bad Cooper, who “represents” the macho in the show (in his debut scene, Otis in the cabin affectionately calls him “Mr. C,” like calling a pimp, which he sort of is, but of contract killers), who finally, unintentionally, proves the ridiculousness of his toxic masculinity by himself.

FREDDIE & BOB (COMEDY)

Just as the superhuman powers are given to Freddie by The Fireman though the glove, the same are given to him by BOB that resides inside Mr. C, and the suspense almost disappears immediately when he’s thrown into the hilarious “battle” in the Farm, during the first half of Part 13. We see a group of big macho men bragging about how the only reason their boss is the boss is because no one can beat him at arm-wrestling, an instant comedic moment. By the time these words were uttered, it was assumed that the audience had figured out the end of the matter. Of course, what’s most hilarious is that it’s because of this that Lynch can film this group of men with such enjoyment, as we are watching a boxing match where the outcome has long been decided. All the fiery yelling and toothy dancing are turned into pure mise-en-scene display, and it also turns Renzo’s blushed-face into a brilliant comic performance. With that, the seemingly spontaneous passion of violent underground sporting events evaporates.

No wonder Mr. C’s fate, four episodes later, feels so jarringly ironic: first with Lucy’s historical gunshot (Lynch/Frost must have waited this moment for so long), followed with BOB’s black sphere broken by Freddie’s whooshing punches. A comic book treatment for comic book characters. Freddie’s battle with BOB is fragrantly assembled, with Lynch himself filming the shaky footage with a DSLR camera. In its dazzling staging, the flickering and overlapping images, a “fistfight” was turned into abstract art, completed with cheap video effects. It’s a dangerous gesture, paired with the anti-climactic ending of the two contract killers in the previous episode (Jennifer Jason Leigh and Tim Roth, playing as if just came off Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight), killed by a Polish accountant (yet another random personnel), who sweeping them off in road rage with a semi-automatic weapon in a stressful Vegas neighborhood, as commented by the Mitchums. The van carrying their bodies, turtle-like, crawling past the two FBI agents who witnessed it, lazily stepping onto the roadside grass. The death of the killers, the destruction of BOB, and Freddie’s superpower, like the sudden acceleration of pace and explosive plot progression of Parts 16 and 17, can be seen as a seemingly rushed disruption on the overall tone and pace of The Return, but it is also a warning from Lynch. The point was to let the audience consciously feel that the ending of BOB was wrong, that this original series’ most terrifying demon, who tormented Laura Palmer in Fire Walk With Me and beyond, shouldn’t just “die” like this, haphazardly destroyed underneath the “ugly” digital effects. Isn’t that so? But at this point, after a tiresome yet intense journey, everyone wants to be Freddie, and the desire for a happy ending and reaching the “destiny” was so strong that a brief loss of memories occurs. We accept that Lynch, a notoriously uncompromising filmmaker, has been generous enough to give us beautiful fantasies (not unlike Mulholland Drive, but this time far from just a dream), only to not know that there’s a whole hour and a half of unexpected twists and turns to come.

JUDY

But in a way, perhaps BOB and Mr. C should’ve been so “sketchy” destroyed. Because they were never the source of the problems. Rightfully, they represent absolute evil, but all absolute evils, as all physical entities do, always turned out to be not the most terrifying. Did BOB cause Laura’s death? Yes and no, because Twin Peaks is, in its core, a story of traumatic, abusive and incestuous relationships in an American nuclear family, and even as the original series tried to draw the line between Leland Palmer and BOB, Lynch shows quite clearly in Fire Walk With Me that the hole in Leland’s consciousness as a father, his tightness and cowardice, was the thing that eventually evolves into violence. Was BOB the source to Cooper’s imprisonment and split? Again, yes and no. “Mr. C” might just be part of Cooper’s inner self, and the coffee-loving, tree-smelling Cooper as well, and at the end of Season 2, it’s the “whole” Cooper who voluntarily accepted the deal with the demons, a mistake which he will make again with bigger consequences. Lynch himself, as Gordon, opens the penultimate episode of The Return with a sprawling explanation and backstory of “Judy,” which at once seemed tempting, but yet seems to be another red-herring. What drove the mysterious FBI deputy director to suddenly start exposing secrets that he hadn’t wanted to mention for 25 years? Gordon tells us that “Judy” is an extreme negative force, and we immediately begin to look for entities in our library of images: is it Sarah, parasitized by jaw-dropping dark energy? Was it the phantom that killed the New York couple? Or rather Judy’s in Odessa, Texas?

Perhaps all of them, but perhaps neither, and if Part 18 proved anything, it demonstrated a misunderstanding of physicality, of symbols: when you think being trapped in the Red Room is the worst fate for Cooper, perhaps it’s not so simple. After all, even if the Red Room seems to be an abyss, it’s still just a “room”, a place Cooper will eventually “leave” one day. And when Cooper was split into multiple forms, we said to ourselves “no worries,” because the narrative demands that he’ll have to come face to face with himself anyway…… But what if he enters a realm that has neither exits nor entrances? What if this realm is our real world? What if he is at once a complete personality, but being totally different? Lynch’s spectrum ultimately proves that any surreal imagery is no match for the irony of reality itself: an infinite night drive, a 24-hour diner which lights are now darkened, or just a plain old family house in Washington State. As defined by the American writer David Foster Wallace after seeing Blue Velvet, Lynchian is the creepiness behind the every-day and the mundane. Of course, it takes a dialectic between surrealism and realism to catalyze these secrets, as revealed by the childlike drawings in Cooper’s case files when he was trapped as “Dougie Jones.”

DOUGIE JONES

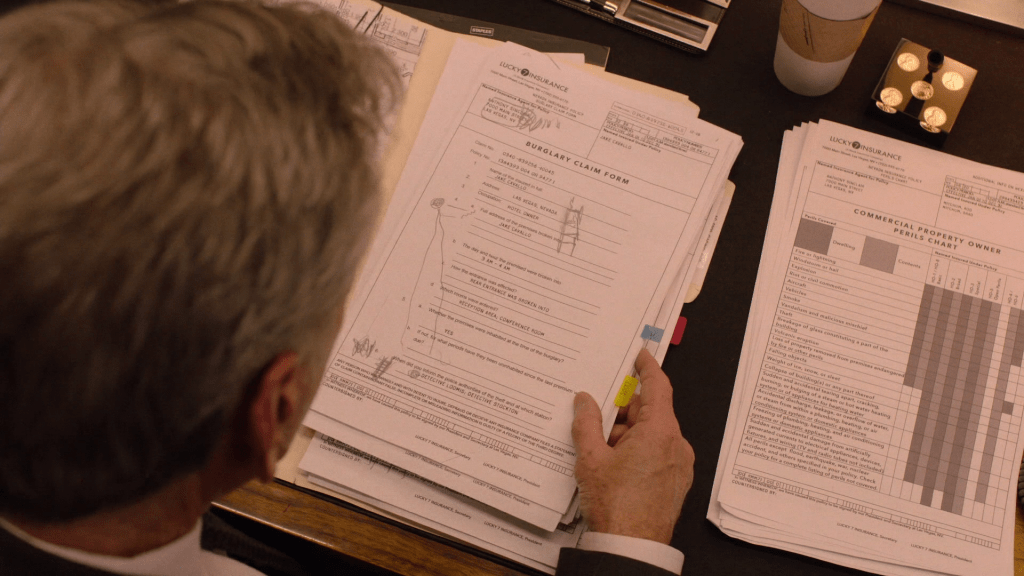

Dougie Jones, what a common name: “Dougie” is the kind of nickname people use for their puppies, and “Jones” used to be the featureless surname that David Bowie (born David Robert Jones) chose to discard when he started out as a musician. Clearly, Dougie doesn’t possess all the aura Cooper once possessed: with a deplorable taste in suits (even Lynch shoots with grotesque beauty) and a wig on his head, Dougie with his fake belly, lies on a plain mattress in an empty Vegas house. It’s the worst look Cooper can be, and even less so for Bad Cooper, who at the very least has the villain charm floating around, while Dougie can only squeeze a few smiles out of his face, more ridiculous than any surreal special effect. Just when we’re still wondering what the hell this man is, he disappears into the underworld (Part 3 XbjVDRiY) and is replaced by the real Cooper, who falls into a half-sleeping state. Just when we think things can’t get any worse, we have to watch the almighty Twin Peaks No.1 man turns into a complete stick, stuck in an even worse identity: an insurance agent with a shaky position at his company, Lucky 7, being hunted down by a criminal gang, and a miserable gambler with loads of debt, plus disowned by his wife for cheating.

Yes, we need to talk about Dougie, not the gambler Dougie in the dreadful yellow suit, but the “Dougie” that had Cooper sleepwalking for thirteen hours. Twin Peaks: The Return is undoubtedly a collision of polarizing ideas, and if this work is a miracle, the appearance of “Dougie Jones” undoubtedly symbolized the infinite ecstasy of that miracle, as Lynch says, “To chase away the darkness, all you have to do is turn on the lights.” The incomplete Special Agent Dale Cooper becomes “Dougie”, a sparkling force, and we are reminded, in the most primitive yet radical way, of the virtues of this blissful classic hero. This silent child, who carries the gravity of the supernatural realm, dispels all hypocrisy and evil; he recognizes deception at a glance; he condenses and simplifies language; he restores the harmony of the nuclear family, and purifies the minds of his rivals; the forces of evil are rebounded by “Dougie” like magnets of the same pole. Yet this is also the saddest irony of Lynch. “Dougie,” after all, is an “unnatural” artifact. Being in Cooper’s body, he remained a tulpa, an idealistic image of a do-gooder, like a “dumb student” who suddenly gets a perfect score on an exam, standing alone under a statue of a western cowboy (Part 5, in a most romantically sad end credit scene), whose luck and good fortune belongs only to the form of cinema: a story destined to take place in Las Vegas, a rhapsody in purest Vegas form.

This love of Dougie is not a call of unwarranted enthusiasm for childish imagery and optimism, because Lynch’s staging never lacks suspense, so much so that Lynch slows everything down to make you care about him. You feel this new-born body strolling, occasionally crashing into a glass wall; he triggers the craziness in the casino, breaks through the hypocrisy of these dazzling slot machines, the sound of the alarm bell (does that signify “arrest me” or “reward me”?) accompanied by the jingles of coins, creating music with “HellooOoOoOooo!”. “Dougie” is almost M. Hulot from Jacques Tati’s comedies, the lost sensory of his body instead brings movements to all who intersect with him, his clumsy body movements magically make others feel emotion, and you’ve never been able to look so closely at the face of Kyle Maclachlan, the old friend of Lynch, where the loss of time and memory reflected in his silence and stiffness. He sees dandruffs, looking like stars, on the suit in the back of corrupted employee Anthony, who tearfully decides to change his heart (“Fix your hearts or die!“, recalling a story with Denise, Gordon commands with passion in Part 4); Janey-E, played by Naomi Watts, feels joy once again, and also gets to spew out her inner rage towards this world of capital and bureaucracy (against two bookies, she couldn’t be tougher in Part 6, a declaration moment for the politically-active Frost, à la Dr. Amp); the seemingly stereotypical gangsters, the Mitchum Brothers, goes into a binge upon meeting him, dancing in conga line; and Dougie’s boss Bushnell, a former boxer, finds the charm of transcendence. In Part 6, when Bushnell sees the scribbles of “Dougie” on his case files, first confused and angry: “How am I gonna make any sense out of this?“, in which “Dougie” softly repeats, “Make … sense of it.” Voilà, the man understood it well.

Completed with a new Badalamenti tune titled “Heartbreaking,” when the wandering old lady from the casino (Linda Potter), suddenly dressed in all her splendor, accompanied by her son, emerges in Part 11 to thank “Mr. Jackpot”, our hearts jolt. The audience hits the jackpot: the most unexpected emotional moment in the series, like something came out of any ending of Frank Capra movies. It took a 30-million dollar check and a whole cherry pie to get Dougie off the hook from the gangsters, while two slot machine jackpots worth $28,000 morphed the seemingly worthless gamble addict into one of the most moving characters in The Return – and truth be told, no one would expected, or would have cared for her return. But Lynch and Frost brought her back, not just to show us how a poor old lady got rich overnight, even with far less money for her than for “Dougie”, but it doesn’t matter. Both authors want us to see how she breaks free from the image of the cynical Slot-addict in the third episode, and blossoms into a surprisingly dignified, generous and full-bodied personality: she looks at the wordless “special” agent as if one of her own. Her fancy dress and house and her new dog are not just some wanton consumption in the name of neoliberalism, and Lynch only serves to prove that this little push from a “Dougie,” even if it still resides from the absurdity and hypocrisy of Las Vegas, can change a person’s life. We won’t see her again after this episode, but the image, the music, and the performance are enough to make us believe in a bright future.

BELIEVE IN DOUGIE

Waking up from the dream, Cooper tells MIKE to build a new Dougie out of “seeds.” The latter opens The Return‘s Part 18 by fulfilling Cooper’s promise to Janey-E and Sonny Jim, knocking on that red door and bringing a new family to their happy ending: the only happy moment of the episode, and after which things will drive darkly toward the unknown, away from the nostalgia and idealism of the last two parts, and back into our trapped reality. Here, Lynch and Frost remind us of the illusion of Dougie’s nature, but at the very least, his greatness can be revisited in this series, as an ideal “Dougie” is still not worthless. Yes, as Cooper sinks into the misery of “Richard” by desperately trying to change the past, we instead begin to miss “Dougie,” the irritating, clumsy, “a waste of time” for the audience. Believe in “Dougie!”

THE MESSAGE

“Hawk. Electricity is humming. You hear it in the mountains and rivers. You see it dance in the seas and stars and glowing around the moon, but in these days, the glow is dying. What will be in the darkness that remains? The Truman brothers are both true men. They are your brothers. And the others, the good ones who have been with you. Now the circle is almost complete. Watch and listen to the dream of time and space. It all comes out now, flowing like a river. That which is and is not. Hawk. Laura is the one.” —— Margaret Lanterman, Part 10

TAPE RECORDER

Meanwhile, in South Dakota, anticipating a pending ambush, “Bad Cooper” surrounds the defenseless Darya at a motel, and we immediately perceive danger and even death. Male aggression against women continues to be examined in Lynch’s work, from Dennis Hopper and Isabella Rossellini in Blue Velvet, to William Dafoe and Laura Dern in Wild in Heart; Twin Peaks is even more representative of this. And all that’s left of this eight-minute interrogation scene is Darya’s desperate futility and Bad Cooper’s absolute indifference, and the audience already foresees the ending. Lynch, meanwhile, reinforces the cruelty through the overlay of action and lines as Darya repeatedly tries to escape, as many as four times, and each time pulled back by Cooper, unopposed. Tight two-shots of the characters make watching the scene all the more upsetting, forming a kind of terrible neutrality hidden in the non-point-of-view. MacLachlan’s performance is superb here, in the sense that we can’t connect the character to the “real” Agent Cooper, yet it is a phone call that Cooper intercepted through a portable recorder that triggers the conflict, and nothing could be more horrifying than Cooper pulling out a black tape recorder at this moment. Anyone who has seen Twin Peaks will immediately realize what the tape recorder means to Cooper as a character – the presence of the yet-unseen Diane. At one time, we were always watching Cooper report to Diane via the recorder, first as it introduced the agent in the car on his way to Twin Peaks, and then at the Sheriff’s Station, or in Room 315 at the Great Northern Hotel, and so on. The character, who never made an appearance in the original series, was arguably the perfect partner for Cooper. Now, Bad Cooper debuts with a similar portable recorder, and while it doesn’t shout out the iconic “Diane…” intro, it’s certainly a terrible hint: what happens if he turns even this closest of partners into a puppet possessed by evil? As an audience member, I remember clearly how I couldn’t face that possibility myself.

“DIANE……”

Although we don’t realize until the finale that Diane had already appeared in the third episode of The Return in a hidden form, her actual debut in Part 6, played by Laura Dern, was still a surprise and a cautionary move. Cooper’s first line in the entire canon of Twin Peaks was shouting her name, and from the beginning, as an invisible character, Diane was as familiar and as alienated to the audience as Laura Palmer. Like the supernatural forces that haunt the entire series, whether it’s the dead Laura or the unseen Diane, who always appears only in Cooper’s lines, these invisible characters or forces are always enveloped in the world of the show, and they are more or less represented as passive objects. Thus, when Diane appears physically, the object being represented suddenly becomes an autonomous whole, just as we don’t witness the true essence of Laura until Fire Walk With Me, an atmosphere of unknowing mystifies of the character even more, making her whole truth a labyrinth to discover. Eventually, in Part 16, we find out that the silver-haired Diane is not the real Diane, but rather a puppet controlled by Bad Cooper like the original Dougie, as the black tape recorder in Part 2 suggests, except that Bad Cooper doesn’t hold onto his recorder like our beloved agent does, and this evil-possessed killer simply uses this Diane as a tool, like one of his disposable cell phones.

DIANE

Lynch and Frost gradually unveil this version of Diane in a very provocative way. Her crude language first breaks down our stereotypical perception of this secretary figure (“Fuck you, Gordon“), and then in Part 7, with her pivotal conversation with Bad Cooper in prison, we realize that there’s a terrible history that thoroughly alienates the duo. Doing speculations is easy, but we prefer not to take it as truth, even if all the evidence points to that one and only possibility – that during the 25 years of Cooper’s disappearance, Bad Cooper sexually assaulted Diane like Leland/BOB did to Laura (a story finally told in the most painful way in Part 16, with one of Dern’s best performances). This dark core of Twin Peaks remains as frightening and unsettling as it was in the early 1990s. In the year when Laura’s murder was still a mystery, bets were placed on the question of “who killed Laura Palmer?”, but not surprisingly, Leland Palmer came in at the bottom of the list – no one wanted to believe that the grieving father was the source of horror, just as Ray Wise, who played him, didn’t want to believe that, even after his character had murdered Jacques Renault (which we would say was justifiable if we were used to revenge plots), his hair turned silver like BOB overnight and he danced like the little arm of the Red Room.

“What year is this?” The answer: 2017, the first year of Trump’s America, the first year of the #MeToo movement. Our nature dictates that we don’t want to hear the worst, just as when the man who assaulted the young woman in the Roadhouse was revealed to be Richard Horne, we’d rather not believe the truth even if we had sensed he’s bound to be the bad seed that Bad Cooper planted by raping an unconscious Audrey in the hospital twenty-five years ago. We try in our minds to delay the truth. The irony is that we are, again, so eager to know the truth, so eager to put an end to things so that we can forget and move on. Diane’s case is more complicated, as we realize that she is perhaps an accomplice in Bad Cooper’s plan, in addition to being his victim.

Let me reminisce on the 105 days of my own journey when I first saw The Return. When Diane receives the first mysterious text from Bad Cooper in Part 9, the possibility of a villainous Diane is slowly built up, something I didn’t want to believe. One unconsciously rejects the thesis: “Diane couldn’t have done that!” Unfortunately, anything is possible in the world of Twin Peaks, and more evidence comes to light: she witnessed Bill get his head blown off and did nothing, peeped into the coordinates Albert got, and leaked information to Bad Cooper. But like the “real” Diane at the end of the episode, the “fake” Diane was presented in such realism, because even as a “Tulpa,” she is completely different from the original Dougie, thanks to Lynch and Frost’s blurred interpretation, and Dern’s layered performance. How can the extreme emotions she displays in many moments remind us of her programming behind? This Diane, though a “replica”, is a different kind of split personality, and her aloofness and crudeness does not mean that she cannot summon the “real” Diane from time to time, far far away. “Oh, Coop…“, Silver-haired Diane, who softly calls out in shock when receiving the ultimate mission from Bad Cooper in Part 16, is clearly the real Diane, calling the real Cooper (just woken up from the “Dougie” dream) in her own voice, not the “fuck you” Diane. When Laura Dern battles the demonic past in silver-haired Diane’s final moment, an invisible fistfight, it is the real Diane telling the villainy of Bad Cooper, and the real Diane guiding the way to the FBI agents trapped in the hotel (they’ve been that way for five episodes), and it is the real Diane who cries: “I’m not me! I am not me!” She must draw her revolver and point at her old friends, because only by doing that will she be free from Bad Cooper’s grip, an act rooted from the same sacrifice that Laura must take when she confronts her demons at the end of Fire Walk With Me. Therefore, before being destroyed, she is able to burst one last F-word at the Red Room (plus, indirectly, at her abuser who initially called the assassination) with great pride. The great paradox of silver-haired Diane.

TIME

“That depends on what time it is. I mean, sometimes there’s not even enough time to think of anything. One time, Andy was even thinking that the clock had stopped, and then we realized that we didn’t even know what time it was. It seemed like forever.”

This is a phrase by Lucy from Part 10, and when we look at the variation of rhyme across the entire return season, it’s not difficult to observe that after the cosmic display of Part 8, Lynch and Frost seem to have slowed down the frequency quite a bit over the next five parts (i.e., Parts 9 through 13), and what this brings with it is what Lucy calls the confusion of time and the stagnation of movement, especially evident in the scenes within the town of Twin Peaks. In Part 9, Bobby, Hawk and Sheriff Truman arrive at Bobby’s mother’s home, who gives them the secret message the Major left behind, prompting them to go to “Jack Rabbit’s Palace” in two days. Yet this set piece doesn’t take place until Part 14 (five weeks after if thinking in weekly broadcasting term), after which the series will begin to punch its speed toward its inevitable end. Even the linear chronology breaks down during those five episodes: Bobby goes to dinner at RR’s in Part 13 and runs into Big Ed Hurley, at which point he claims to have “found something his father left today,” an obvious contradiction in timeline. The possibility of a time vortex is constantly hinted at: a recurring loop of boxing match footage on Sarah’s TV (Part 13), reappearance of Roadhouse bands from early episodes (Au Revoir Simone and Chromatics), Diane’s messy texts, etc. There are even what appears to be deliberate incoherence of continuity, which could be an entire essay, but then it is almost impossible to distinguish between real continuity errors and deliberate designs – the heated debate, regarding the inconsistent diner extras during the end credit of Part 7, absolutely confirmed this. Even more coincidentally, if one looks closely at the clues given in the series, it’s precisely during Part 9 that we first learn when the series itself takes place in time: September 29th! And in the previous eight episodes, all the times and dates are deliberately voided except for the two years given in the flashback and “253” when Cooper leaves the Red Room. Let’s recall the clear timing of the originals: Fire Walk With Me limited the timeline to the week before Laura’s murder; the first two seasons of the show proceeded at a strict one-day-per-episode rate, and even in Cooper’s first line of the entire show, he was broadcasting the time and location: “11:30 a.m., February 24th, entering the town of Twin Peaks,” and the FBI agent then proceeded to broke down all the locations he’d passed through one by one. How did we get to this point where making sense of time is so difficult? In The Return, the smooth flow of time-space continuum is forbidden, as if the episodes have left physical time behind, operating purely in the linearity of cinema.

And this brings yet another paradox, because in countless extended scenes during The Return, time stubbornly passes in a delicate and steady motion, as if we are forever trapped in the speed of reality, and the work makes us feel every passing second. At this point, the speed of this apparent reality also seems to be somewhat surreal: Dr. Jacoby slowly airbrushes his shovel (Part 3), and while filming his mundane routine, Lynch seems to invoke himself finishing a piece of furniture or painting in his Los Angeles studio; in Part 7 we watch a man sweep the floor for a full two minutes; in the next episode, another two-minute shot slowly pushes toward into the world’s first atomic bomb; evil reptilian creatures slowly hatch from an egg in stillness; the girl falls asleep in bed and is slowly parasitized; Gordon, Tammy, and Diane stand quietly, smoking in front of the Buckhorn police station (Part 9); the French woman comically gets up to leave, and while Gordon watches in fascination, a tired Albert silently watching their cryptic game (Part 12); “Dougie” and Janey-E’s nearly fifteen-minute confrontation at the beginning of Part 6, and it ends with him silently painting on a table.

These variations on the philosophy of time are perhaps also the appropriate representation of the three bodies of Cooper: the Good, the Bad and the “Dougie.” We are repeatedly reminded by MIKE that “Is it future? Or, is it the past?” We think this as the complete Cooper, who was spilt: FBI “Special Agent” Dale Cooper was dwelled in the past, a past where he was imprisoned, forever haunted by the one he couldn’t save, and then, the one mission he must complete; Bad Cooper sees only the future – his inevitable destruction, and therefore he makes plans and obstacles to prevent it from happening, with pain and sorrow brewing along the way, he drives forever through the night, his tragedy; And “Dougie,” needless to say, is a man of the present, who has no sense of time and yet spending time to their maximum, it is he the “Good Dale” that calls for coffee and cherry pie, the one who says in the original series: “Every day, once a day, give yourself a present.” So, what is the source of chaos? In Twin Peaks: The Return, the arrival of the chaos of time comes from an obsession with both the past and the future, two polar extreme forces that are “nonexistent,” at least in the normal sense, and it is the inherent irreconcilability between them that creates the chaos and fear we experience.

EMERGENCY RESCUE

“Dear Twitter Friends, do any of you know where Everett McGill is? I’d really like to talk to him. Thank you.” —— David Lynch, on Twitter

Twin Peaks: The Return faces, after all, its own passing of time, and it was destined to return around 2015-2017, just as Laura Palmer once predicted. Unprecedentedly, a rebooted sequel chooses to find those lost time regained in the present, in the aging of her actors. We’ve always admired the absolutely beautiful men and women in the original episodes – the love for these actors is magnificent. In 2015, when The Return began filming, Lynch was 69, Frost was 61 and Kyle MacLachlan was 56. The time that belongs to Laura Palmer, Sheryl Lee, wasn’t frozen in that old 1989 photograph or in the face of her corpse; Lynch chooses to let her appear in the Red Room at her present age. The wrinkles of time clearly visible on each returning actor under the high-definition gaze of the digital camera: the traces of age on Laura, MIKE and Cooper’s faces remind us how long those 25 years have passed, even in a field as transcendent as the Red Room that defies the laws of time-space.

A quarter of a century later, aging and death naturally became one of the themes of Twin Peaks. “Do you recognize me?” Laura reminded Cooper with wide-opened eyes, seeming to question the audience at the same time, and we, too, will believe it, like Cooper, who replied, “Are you…… Laura Palmer?” For Lynch, the emotion concealed in between seem to be beyond words, but he chooses to still adopt a dialogical shot-reverse-shot method, but all we can see are two astonished faces staring at each other with tension. Meanwhile in the town of Twin Peaks, illness plagues: Beverly’s husband suffers from cancer and depression; Steven’s psyche crumbles under the influence of drugs and downhill economy; the mundane mechanic living in the trailer park must sells his blood to support himself; “wicked rush” appears on the woman in the Roadhouse; Audrey seems to be living in a mental institution….. In the same year that The Return filmed its first scenes, both Catherine E. Coulson (The Log Lady) and David Bowie (FBI agent Philip Jeffries) fought with terminal cancer. The latter chose not to return, but his presence is nonetheless indelible, and how could we let Twin Peaks lost its Log Lady? So the production company assembled a small team at Coulson’s residence in Seattle, directed remotely by Lynch via Skype from Los Angeles (a story that’s especially sobering in today’s pandemic-induced filmmaking hiatus), and filmed the old friend’s last monologues in two simple camera set ups. While The Log Lady died four days later filming her scene, Twin Peaks: The Return quietly turned into a great and sorrowful emergency operation. Marv Rosand, the chef at the Double R diner who only had a few seconds of screen time, also died four days after filming his part; Warren Frost, father of Mark, who played Donna’s father Dr. Hayward in the series, also passed away after appearing in a brief cameo; and most poignantly, Miguel Ferrer, who played Albert Rosenfield, passed away before the show began its run, and every conversation he had in the series with Gordon changed, the uneasy atmosphere that seeped through their humorous chemistry became undisguised; and after the show aired, we saw the passing of Harry Dean Stanton, the great Carl Rodd, the humanitarian glow of this season; also passed away in 2017 was Brent Briscoe, the humorous detective from Buckhorn, who also starred in Mulholland Drive; Linda Potter, who played the casino lady, and Robert Foster – Sheriff Frank Truman, who kept his seriously ill brother Harry in great courage, both also passed in 2019. The good news being: Grace Zabriskie (79) is still around, so does Ray Wise (72, and even in his very short scenes, the complexity in that face still amazes), Michael Horse (Hawk, 68), Richard Beymer (Ben Horne, 82, who still contributed behind-the-scene footage during this production), and Russ Tamblyn (Dr. Jacoby, 85) are still around, and so on. If Twin Peaks should continue in the not-so-distant future, Lynch will bound to be inviting these old friends again, and they will bound to keep shining.

The passing of Peggy Lipton, a.k.a. Norma, was especially sobering, reminding us one of the most precious moment in The Return. In 2014, just a few months before announcing the return of Twin Peaks, in a tweeted message, Lynch requested a phone number from netizens – a phone number that belongs to “Big Ed,” Everett McGill. A Lynchian tale unfolded in reality, as McGill himself recalled that he had been retired for many years, largely in seclusion, and the phone number Lynch eventually got was in fact connected to an old house McGill no longer lived in, but happened to be checking when Lynch phoned it. Thus, like fate, we are able to see the Nadine-Ed-Norma love triangle that spanned a quarter of a century come to a blissful conclusion. Who would have thought that the first scene within Twin Peaks this season, Dr. Jacoby’s appearance, would lead to this “only” happy ending? Part 15, one of the best episodes of the season started with it, and it also marks the beginning of the end. With Dr.Amp’s shiny golden shovel on her back, Nadine strides toward Big Ed, finally embracing him and giving him his freedom with incredible determination. And then in the passionate melody of Otis Redding’s live version of “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” from the ’67 Montreal, Lynch and Frost give Ed and Norma, the long-lost lovers, their ultimate moment, what is there to say? And in Norma’s confrontation with businessman Walter (a delicate detour that gives this scene extra suspense), Lynch and Frost, with hyped spirit thanks to Lipton’s tender performance, declared victory to the great independence, the great moving image, like one of Norma’s cherry pie, organic and local. Otis’s song pauses and plays as this scene unfolds, much as the spark of Twin Peaks dims and shines through its history, but in this moment, Frost, Lynch, Norma, Big Ed, triumphed completely at the Double R – Twin Peaks’s most wonderful place. This emergency operation will be written in the history of cinema, and this museum of Lynchian images and sounds is the most generous and loving gift of the second decade of the 21st century.

THE PALMER HOUSE

And then comes the night, even the Double R closed its light. I was always met with adversity when writing about Part 18, for a part of me will be forever imprisoned in the night of September 3rd, 2017. No, I will not be theorizing, there are a great deal of them where my creativity simply couldn’t match. But what I saw there was a man, devoid of time and stripped of identity, still believing he is “the FBI,” the one who saves the day. He announced that he’s “with the FBI” at Eat at Judy’s; then again, in front of Carrie Page’s house; one more time when Carrie doubted him, and a badge was shown; and ultimately, in front of the Palmer house, where he will say for the last time: “FBI. I am Special Agent Dale Cooper.” Notice how Kyle delivered this line with a subtle questioning tone: this time, he finally starts to doubt himself. But how can we expect him to do otherwise? Kyle Maclachlan and Sheryl Lee, the two figures who will forever be the souls of Twin Peaks, stood there, as it should and should not be. In this empty, confined road, not a soul in sight, the kind of view that will arrive in our reality three years later. What will happen if the man simply continue to lead with all the great people he finally reunited with at the sheriff station, before the blackout consumed him, Diane and Gordon? We’ll never know. So let me simply leave you, my most faithful readers, with this heavily cryptic message:

When interviewed with rare clarity in that December 2017 issue of Cahiers du cinéma I’ve mentioned way earlier, where Twin Peaks: The Return was declared Best Film of 2017 (and ultimately Best Film of the 2010s, two years later) to heated debate (which Cahiers held absolutely no responsibilities), Lynch said the following after some silences: