by TWY

“When agent and effect do not coincide, we have a discordant, dynamic, unreal and fugitive expression.“

—— Johannes Itten, KUNST DER FARBE

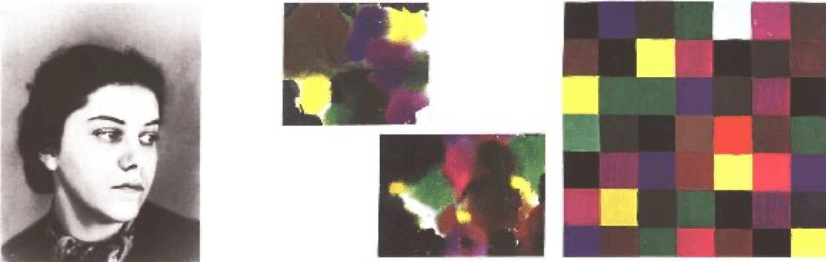

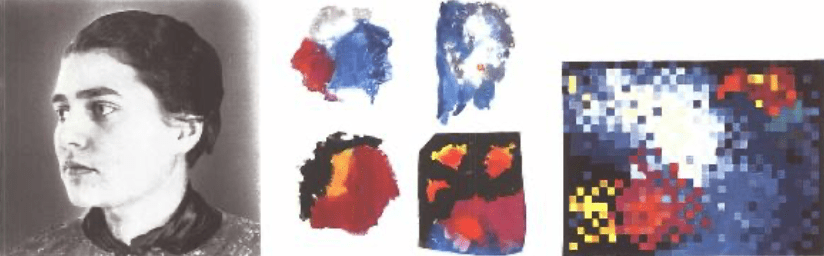

A theoretical text as well as a practical tool, Johannes Itten’s seminal Kunst der Farbe, first published in 1961, begins with a desire for renewal, to learn again the foundational elements of the world. Its full title, “The Art of Color: The Subjective Experience and Objective Rationale of Color”, encapsulates a pursuit on two fronts, where a protege learns not only the “objective principles” of the color spectrum but also the subjective taste that defines each individual. Before Itten introduces “the seven color contrasts” that constitute the main body of his text, he first displays an experiment, using the musical term “subjective timbre,” where he lets students to draw color combinations that they believed to be the most harmonic (see figures below). In these countless variations of “subjective colors,” what’s revealed then are the irrational sensitivities amongst each person whose choices of palette and proportion display an essence of their souls. We can already point out that, for Itten, there is no such thing as “a pure color” but relations between colors, a “montage” inherent in its nature. The book, not simply a text about the vision, is also one that communicates with the language of other arts, punctuating throughout the author’s arguments in his liking of musical or rhythmical phrases. The art of color is the art of collage.

Mariano Llinás’ Kunst der Farbe is not a direct adaptation of Itten’s work, which is undoubtedly not contributed by the fact that cinema and photography, unlike painting and calligraphy, are notably absent from the book’s discourse. Indeed, a painter starts with nothing, and no matter if a work is realistic or abstract, it starts with a blank canvas, and choosing a color always implies a particular rendering of ideas or meanings. Filmmakers, however, must begin with the world, where the camera isolates that world’s totality of hues by framing specific beings. Cinema and photography “replicate” the real, amongst them their full spectrum of colors. But this Bazinian view of realism still does not arrive at any “pure” representation of color since each shot already contain a reality composed of infinite details and associations, always escaping the filmmaker’s mind, which he must discover by looking at it again. The world itself projects its secrets. More importantly, colors in cinema have always been a product of a mixture; from the three-strip Technicolor process to today’s digital color-correcting system, “natural” colors do not exist in cinema as much as they don’t exist in paintings. The very nature of color is dictated by such.

Art and the world (cinema) seem to be caught in a circular conflict of perspectives. Therefore, the idea of making a film “about” color poses its own challenge, for which Llinás returns to his square zero, a “blank” canvas of cinema, which, paradoxically, is already the world itself. But strangely, this desire for renewal, for the Argentine filmmaker, first came from a place of agitation: a break-up between friends. As the author inscribed at the beginning of his film, Llinás was commissioned to film the group of artists known as “Mondongo” as they create an artwork based on Itten’s book. To stage a conversation between the portrayed and portraitist, Llinás proposed a challenge “in the manner of Jules Verne adventure novels”: Each party will create their own interpretation of Kunst der Farbe, which Mondongo didn’t accept. Long story short, the project became a triptych, and Llinás and Mondongo ended their two decades of friendship. The first two installments from the cycle, Mondongo: El equilibrista and Portrait of Mondongo, served as documents and prophecies of that ending rapport. (Besides the segments where an argument broke out during a scene between the artist and the filmmaker, how did Llinás find out? Perhaps by being unable to find “a shot,” as he was filming in the artists’ studio.) Therefore, what was originally a singular piece became three films, solitary from each other.

As Cyril Neyrat, programmer of FIDMarseille (where the trilogy premiered), wrote, “The duel never occurs and Llinás ends up making his film alone, or with a few accomplices who are delighted to play along.” Nonetheless, beginning with Itten’s text, Llinás goes through a diagonally different approach. What are the subjective colors for Llinás, whose films are fiction, adventures, collaborations, portraits, and duels? Llinás’s film is surely not a lesson for aspiring designers and painters (or even filmmakers); he is rather interested in re-educating himself, separating “his” spectrum of colors (physically and metaphorically), and dissecting the alphabet of his approach to filmmaking as well as his canvases. Unlike the painters’, the canvases for him are the actors, the camera, the landscape, and the digital tools, which are deeply impure, with their obscene level of manipulative power, but still alluding to a kind of freedom. And if the language of music, for Itten, provides a pathway to describe the secret rhythm of color, Llinás will accompany his film with a wall-to-wall musical score composed by his trusted colleague, Gabriel Chwojnik. Finally, there is also the absence of his offscreen voice-over. For the first time, the great narrator may have finally exorcised himself from the devil of words.

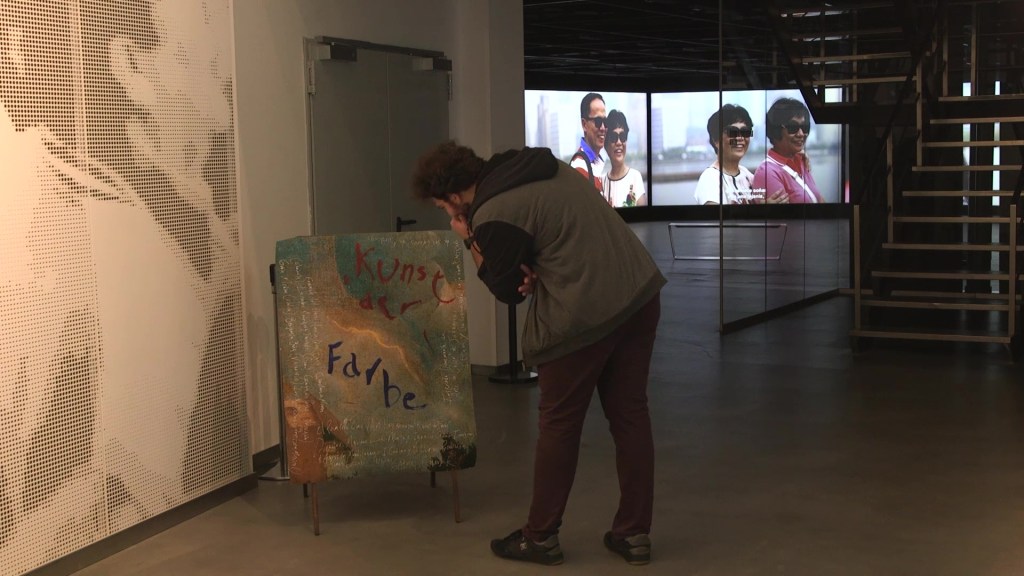

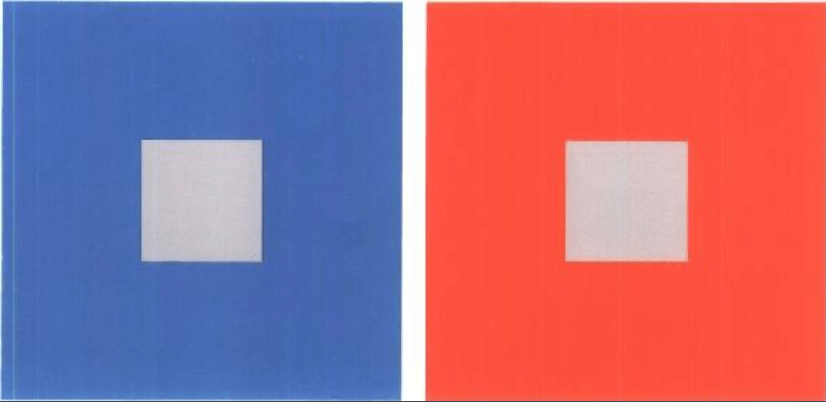

There, in music, the filmmaker finds a space. In fact, the film is several places intersecting at once, serving as his canvas. If Llinás was visibly not “at home” at the studio of Mondongo, this time, he compels to find his own kingdom. A delightful opening sequence: we are outside of a door at a gallery, with a poster of a show for “Kunst der Farbe” – we enter a concert hall to see a performance of Chwojnik’s opus. But, already, there is a twist: the unexpected juxtaposition of Louie Feuillade’s Les Vampires (1915-1916), the classic serial where a journalist investigates and combats an organized crime syndicate called “The Vampires.” There, a scene from a century ago, the same thing: a group of spectators is at the door of a cabaret, where a poster announces a show by “Irma Vep,” which one character recognizes is an anagram for “vampire.” (Word games will arrive later in Llinás’ film as well.) As we enter the theater, there is Musidora, enchanting the audience with her hypnotism. Through an impulsive frame-within-frame, Feuillade’s film is summoned as yet another container (its black-and-white images are tinted with different hues); or rather, Llinas’s images will graft with Les Vampires: the theater we are entering into leads to both places, in an entanglement that connects two histories and two times. Often appearing in the center of the frame as surrounded by raw colors, Feuillade’s monochrome images become the “gray” center that serves as the counterpoint of other hues, like the gray squares from Itten’s book that demonstrate “the psychophysiological reality” of color perception, where gray turns reddish when surrounded by blue. Les Vampires, for Llinás, is the reflector of the world, the fictional material vibrating with the chromatic of the real.

There begins a film, with its breathtaking pace, that avoids accumulation of too much concrete meaning, as the rapid montage stirs the images, mixing colors of the real and the artifacts, from the heightened red on a roadside shed to the washed out blue of the sky – we are encouraged to see their contrasts and fluidity. Each chapter/movement, with its cryptic title (for example, “Blue, His Majesty, Prince of the Air“, or “White, or the Demon“), focuses on one color, and yet, inevitably, also invites the opposing or neighboring one. Llinás and cinematographer Agustín Mendilaharzu begin by searching in the provinces, along the roads and the plains, following vehicles and vegetation. Simple lessons on framing ensue. The empty billboards, with their bulk of blue or red, form the first prototypes – screens to be projected. The rule: No color stays solitary, as with any landscape. They are accompanied, in editing, by the movements of musicians, paintings by Giorgione or Paul de Limbourg, the actresses and the filmmakers, and later, the film’s colorist.

Then, a series of complications. A blue billboard turned red. The entire landscape, as well as images from Les Vampires, is tinted with artificial colors. Multitude of the images in Frames within frames. A color “role plays” its neighbor. A blowup painting is revealed as pixels. The film situates itself in the era of digital images, a time where it’s hard for a filmmaker to renew his senses when cinema is so far away from the chemical “lushness” of Technicolor, where the digital tools allow for “absolute” precision in color correcting, which, paradoxically, can only be completed with an opposite procedural: images shot “without” colors, in a neutral grayish tone from which colorists begin their work. The first movement of Llinás’ film, thus, explores how, in the digital canvas, all colors have become interchangeable. (Apart from mainstream films that seem to process similar color palette, think also restorations of classics that carry dramatically altered brilliance and/or color temperature from previous home video releases.) The filmmaker hints in an interview a sense of perversity, a fanatic desire to distort the images: to create blowups of Giorgione’s The Tempest, to tint the “raw” pictures of landscapes which made them surreal objects, in the sense that the vest tint of the hue destroys the illusion of naturalism. To vampirize the image with the digital shadow, drowning all its tones, while the shadow’s flickering becomes rather exhilarating for its transport between real and surreal. Therefore, there is a particular emotion when the camera simply “discovers” a color. A yellow car, which the filmmakers follow in a Hitchcockian manner, thus ceases to be merely a vehicle but a monstrous object with a secret destination – we remember it as we remember, in the opening shot of Marnie (1964), Tippi Hedren’s yellow handbag. There is also the grayish blue on the sky, accompanied by the curve of a plane, a magnificent cow passing a meadow (the color brown), or a wheat field illuminated at sunset, reflecting a gold that is the evidence of the earth, where the green exterior paint of a harvester slowly emerges as it drives through the sunbeam. In this gold, which is the embrace between light (the sun) and matter (the earth), as explained by Inés Duacastella, the film’s colorist sitting at her workstation, one can finally look back at the work of the expressionists, who took their canvas to the open to look at the world, to say that their colors came from that world as well.

This roleplaying only continues beyond the realm of sense. Llinás continues here an art of cinematic sketching, something he has been practicing since La Flor (2018): short, compacted skits played with actors in costumes, not yet completed scenes but rough ideas of them, often shot in the office of El Pampero Cine, his cherished family. Here, the color of the actresses, Pilar Gamboa and Maria Villar, who interpret, respectively, Juliana Laffitte (one of the Mondongos) and a “variant” of Itten (presumably). Stunningly, Llinás plays Fritz Lang, but hardly as a character but an imitation, a gag, completed with the master’s eyeglasses. The two women, who are tasked to reenact fiction, remain undoubtedly themselves. Still, in their costumes, their presences evoke different personas that interact in a totality that is no more mysterious than “pure colors.” To show the actor thinking, rehearsing, and playing around with a text is to believe cinema is an art that thinks for itself.

Nothing shows the way Llinás contorts his material better than the strange staging of a comedy where he reads aloud, like someone learning a new language, the original German text of Itten’s book, in front of a visibly amused Villar – the grin of the actress reaches the same abstraction as the mystery of nature. Hilariously, Itten’s treatise, which is hardly recited for the film itself, transforms into a language lesson, with the German-speaking actress assuming the role of a schoolteacher. One of the pleasures of seeing an El Pampero film is the (apparent) transparency of seeing the filmmakers at work, and we rarely see a filmmaker practice with his actors in such openness, with a lot of humor. And with Gamboa, already an intense presence in La Flor, Llinás takes a chance to review his failed communication with the Mondongos, but this time to examine it within the realm of his art. Through this parody of mannerism that he plays with the actors, Llinás reveals a truth through intonations, with the immediacy of a performance that nulls the incompleteness of a project – he who plays clown in a duel with himself, but through the collaborative joy where comedy, coexists with melancholy, forms the gesture of cinema.

留下评论