WARNING: Contain minor spoilers for Mulholland Drive (2001) and Twin Peaks (2017).

David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive is a continuous flow of poetry, suspense, comedy, screwball gesture, and at its core, blinding, tragic love. Even before its central mystery ultimately unveiled itself beyond the film’s initial existence as an unaired television pilot, it’s the Lynchian touch perfectly balanced in its anthological structure and a collage of diverse characters. It begins with an accident, and somehow, the film dives into a succession of accidents, some quite literally, and others more difficult to define, and some not at all. If cinema had mastered the ability to lie and manipulate, Lynch’s film seeks to understand that lie, and the first lie it dissected is a familiar one: “it was an accident.” The ultimate denial.

Here is the paradox: Lynch’s characters are, more often than not, honest people, no matter if they are good or evil or something else. Speaking the truth is his moral, unless it’s unspeakable. But how to maintain this moral when the whole film played out like denial, or in fairy-tale term, like a dream? The film, then, shows us the ultimate accident, which is the accident of accidentally witnessing the truth: truth about one’s unfaithfulness, about an industry’s dirty secret, about one’s inability to understand his ego, or more simply, about a cup of coffee, etc. Such truths can be quite hilarious to witness, because Lynch is never not funny, but when it’s dark, it’s dreaded in millions of emotions as if this darkness is ancient and beyond our understanding.

How else can we explain the horror of the Winkie’s diner scene, with those characters we will not see again for most of the film? Or how can we explain the brilliant yet disturbing comedy of the contract killer’s series of missteps? And somehow, no matter how many times we see the film, none of this darkly comedies in daylight seemed out of character, when we see Betty’s (Naomi Watts) arrival in Los Angeles, or her bewilderment to discover her aunt’s Hollywood apartment, or the joy of hitting that “perfect audition.” But maybe the situation is the other way around, maybe there are the others, and they are all “in our house now,” to quote one of Twin Peaks: The Return’s most haunting lines, and it’d only come together with Lynch and editor Mary Sweeney’s wonderful wielding of different tones and moods, swinging back and forth on the full spectrum of feelings. For Lynch, the flow of energy and emotion is beyond narrative and individual character arcs, as one person’s emotion are transferred, re-contextualized, reversed, parodied, or straight-out remade to another, sometimes even without the emotion “host” being conscious of it (much like how Dale Cooper affecting those around him as “Dougie Jones” in Twin Peaks). The revolutionary structure of the film subverts its realism by dream logic, but Mulholland Drive remains realist, nonetheless, because it showed our desire most intensely, and not only the desire to have a good life, but to understand why that desire in reality feels so terribly “wrong,” like the man at the diner seeking out the nightmare that inhabited his dream in reality: to get rid of this god-awful feeling. By showing us the dream first and not the “reality,” we are avoiding the trap of cliché, because empathy comes not from eavesdropping on trauma, but to understand the heart of a desire. The desire to understand desire, that’s Lynch’s project.

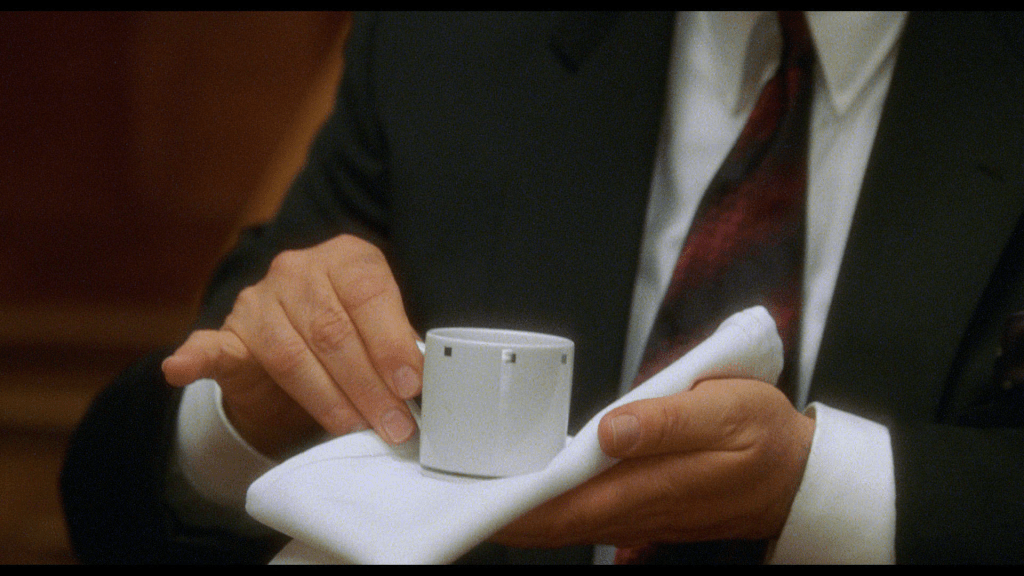

As it was in the beginning, this dream in Mulholland Drive is not always a fairytale, but it’s always funny, that’s where the coffee scene comes in. A young filmmaker, Adam Kesher, is recasting his lead actress after a woman’s disappearance, and we suspect that this woman is indeed the disappeared Rita whom we know from the film’s “other” plot. In a room of claustrophobic quality, with its wooden and narrow decor, the filmmaker is surrounded by his agent, two studio executives, and two Italian producers slash mobster-archetype. The atmosphere is that of a police interrogation (or worse), but the audience’s attention is almost immediately shifted to a seemingly minor detail: the Italian (Angelo Badalamenti, Lynch’s longtime composer) and his high standard for espressos. This side quest hijacks the scene’s main plot, which goes nowhere at the moment – the director bluntly refuses the appointed actress. For a minute, all eyes are on the coffee, in its tiny espresso cup, hand-delivered by a bulky waiter. The feeling is ominous, but still with clarity: Badalamenti is not gonna like it.

This detour to the coffee is worthy and so funny, because for Lynch, the foundation of a scene is in our senses, and all of our feelings are shared on equal plates: no narrative linkage is needed, because the scene itself is physical, and watching a person decide if a cup of espresso is good or shit has the same density and weight as seeing a film director being bullied into cast someone he doesn’t want. They hide nothing, even if it embarrasses them, like in a Ernst Lubitsch film, with the studio executive, the involuntary mediator, standing awkwardly in the middle. Thus, strangely somehow, by witnessing Badalamenti’s sorrowful sipping of his coffee, the pain on both sides are felt, through this incredible gesture of comedy and sensation, and it can only be explained by feeling and not by logic. In the end, we will finally realize it: what we have witnessed in that conference room wasn’t the pain of those two opposing forces, but that of one suffering soul, despite that doesn’t change the scene’s humble and sobering materiality.

It would be a mistake to view Lynch’s oddball creativity as the result of alcohol or other hallucinatory substances, for his driving force is the clarity of ideas, no matter how ambiguous they might appear on screen (for him and for the audience), and more often than not, a cup of coffee is just a cup of coffee, and our filmmaker isn’t speaking in codes. We will have no idea what poor Adam Kesher thinks about regarding his enemy’s hate for a shitty espresso (he yells: “What is going on here??!“) – he probably has no time to think about it at all, only to rush home and find his wife having an affair: another “accident” above Mulholland Drive. But a bad cup of coffee sure does encompasses all that’s painful and sorrowful in a character’s life.

留下评论