by TWY

Despite being rightfully hailed as “the master of body horror”, David Cronenberg has another life-long project, which concerns the act of speech and literary adaptation (William S. Burroughs, J.G. Ballard, Don DeLillo, to cite a few). Such notion is unsurprising, giving that for him, the art of cinema, like the human body, while function as a system of senses, is also a vessel for language, therefore thinking. If Jean-Luc Godard, with his chewy Swiss accent, is our greatest essayist who deconstructed the French language, then by listening to Cronenberg’s characters, one senses that the Canadian filmmaker and novelist has completely morphed the English language, recalibrated it as if it’s always being spoken for the first time. For some, this gives a feeling of alienation, and for others, it provides a key to access strange outer spaces and concepts: the insect-typewriter from Naked Lunch would agree.

Consider his second “underground film”, titled Crimes of the Future, made in 1970, the image and sound are non-synchronized, and the sound elements are dominated by noises and a voiceover – voice of a soft spoken male, speaking as if reciting a thesis from an academic journal of the (r)evolutionary biology – all of it being fiction, of course, but told with a sense of scientific authority, combined with the sensitivity of a maniac scientist’s secret diary. More than a half century later, with his long-awaited new feature, also titled Crimes of the Future, while not a remake, such investigation into the speech will continue to exist, but on a more open plane, in which multiple forces seek to use the language, a.k.a. the human body, to meet their means. Per Cronenberg’s recent efforts, the film predictably wasn’t a big hit at Cannes, because it needs to be said that some of this language, like the bodies he filmed, can be a bit too seductive as to fall into obscurity, making us feeling it a bit lost in their secrets. It is, more or less, a monologue film, and inside it, a manifesto film. At the end, which came suddenly, the film left us with a profound sadness – the aftertaste of a great work.

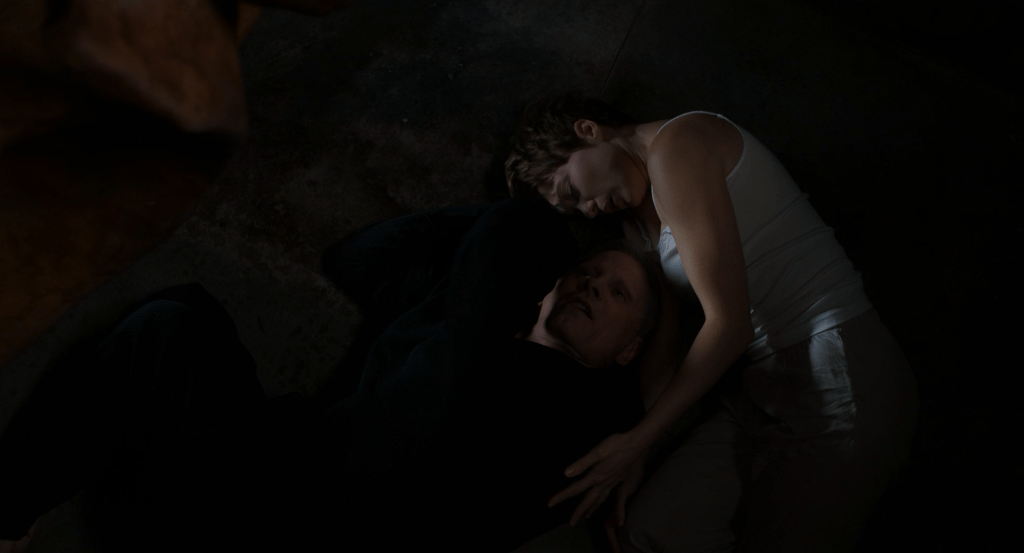

The film operates like a time capsule of Cronenberg’s, as he hatched an old screenplay from the late 90s and let it unfold without altering its time period. In a reality where the human pain has all but disappeared, two performing artists, Caprice and Saul Tenser (Lea Seydoux and Viggo Mortensen, both sensational) have turned surgery into theatre, during which, in front of live audiences, Caprice cuts off strange new organs that are repeatedly growing inside the latter’s body, and as the film progresses, we see that they are not the only one that are creating stuff out of this reality – multiple forces are at play, from the art to the politic to the underground. To take a look at an alternate future from words of the past, Cronenberg eliminates all cliches and influences from our contemporary society (which he had depicted with two great films, Cosmopolis and Maps to the Stars), and invites us to meditate with him. Therefore, no organs of Internet or social media, with a very limited number of screens and cameras, analog, all of which striped of its function to communicate information, in order to be more intimate, all leads to an extraordinary final closeup – while we had expected gore of the flesh, Cronenberg finds emotion in faces and tears.

The real worrisome element of the film, then, no longer lies in media technology, as many of his previous work had depicted, for this time they are all spoken and acted out, with no middle ground serving as agents, thus seemingly reducing the potential genre element into a series of encounters and conversations, continuing the thread of Cosmopolis and not his “older” body horrors. And therefore, it’s clear that not everyone speak the same language, depending on their interests. There are names and slogans – advertising words, often funnily literal: BreakFaster chair, LifeFormWave, New Vice, surround sound, “surgery is the new sex”, etc., with the funniest being “Inner Beauty Pageant.” Gilles Deleuze would be correct to declare advertising as the true rival of philosophy, because it replaces the latter’s purpose to create concepts, and instead, with every “concept” under its name, advertising launches a “product.” But there are other names, more mysterious: Sark, for example, the tattoos on the “neo-organs,” Saul, Caprice, Timlin (very strange character played by Kristen Stewart, with a more chaotic perspective), Brecken, or “Mother”, like the dark and nameless city and her sunken ship, elements that Cronenberg found by accident, when he decided to shoot in eternal Athens. Something are harder to define: a thing, a creature, or a son?

And so, where does this profound sadness come from? It certainly did’t come from the advertisements or any such slogan words that the film had thrown at us (ironically yet fittingly, they are perfect for trailers). In a reality where concepts becomes agent of advertising and politics, it is the artists who choose to remain in the gray obscurity, in the potentiality of meaninglessness, outside of spectacle. It is with the body, because with the body comes thinking, and with thinking comes “the emotional pain of the dreaming”, as Tenser grunts in agony. With his old body horrors, Cronenberg provides access to bodies by sensory, but here, without a necessity to visually provoke us, our body reacts to the act of thinking, therefore to the brain (Cronenberg would say “which is still a part of the body”), to the film’s vortex of an increasingly devastating cerebral theatre, to possibilities of meanings and revelations even the filmmaker himself hasn’t ready to reveal fully. And yet, it seems that morality continues to exist in the dark alleyways of Athens, despite everything fading in darkness, as if the scalpel of the mind bursts out from the frame: is this the future we want?

留下评论